The Great Locomotive Chase: Part I, The Plan

/In 1926, a silent comedy was released staring Buster Keaton as “Johnny Gray” in an action-packed romance set during the Civil War. Not well received at the time, this film is now considered a classic, ranked in 2007 by the American Film Institute as #18 on their list of 100 best movies of all time. Featuring the story of a railroad engineer denied enlistment in the Confederate Army while trying to woo his sweetheart, Annabelle, Keaton’s character is forced into action when his engine, the General, is stolen by Union spies with Annebelle on board. His adventures eventually lead to his commission as an officer and success in winning his girl.

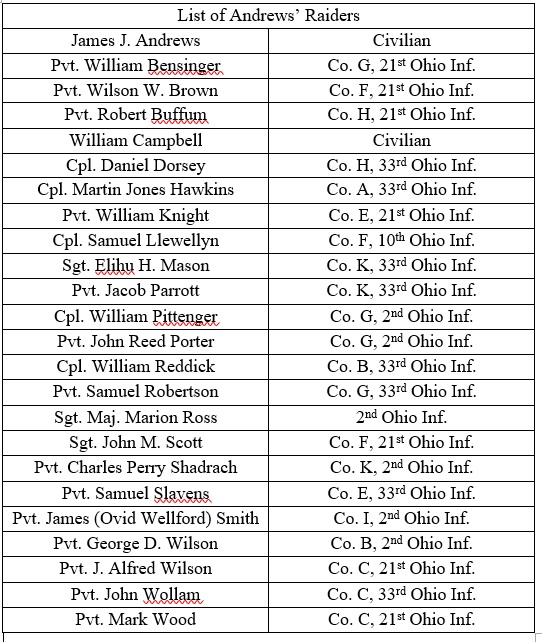

While the story strays far from the original, Keaton and his collaborators based the film The General on a memoir written by William Pittenger entitled The Great Locomotive Chase. At times overshadowed by larger military events, the action Pittenger was involved in was one of the most daring and compelling stories of behind-the-lines action in the war. On April 12, 1862 twenty Union men who had snuck into Confederate territory stole The General and raced for Chattanooga, Tennessee, hoping to destroy railway and communication lines along the way. The end result was both exciting and devastating for those involved.

Chattanooga was a crucial rail juncture for the Confederacy in a state already divided in loyalty between the South and the North. Although the state had officially seceded, much of eastern Tennessee remained loyal to the Union. Recognizing the value of loyal citizens within this part of the state, President Lincoln had already supported attempts to undermine Confederate control in the region. In 1861, loyalists proposed a plan to Lincoln and General George H. Thomas to burn bridges in east Tennessee in order to hamper Confederate ability to move troops, supplies, and information. The Union Army assigned Captain David Fry of the 2nd Tennessee Volunteers (US) to support the actions of local citizens and on November 18, 1861 insurgents burned several bridges in east Tennessee, northern Georgia, and Alabama. Unfortunately, the Union military support wavered and the Confederacy quickly repaired the bridges and executed five civilians as “bridge burners.” After this, Confederate officials cracked down on the region, declaring martial law, imprisoning four hundred Unionists without trial, and threatening a violent response to any further insurgency.

Lincoln realized the advantage of securing eastern Tennessee, but the Army of the Ohio under General Don Carlos Buell moved too slowly for his liking. Fortunately for the President, opportunity presented itself in the form of a civilian smuggler and scout by the name of James J. Andrews. Little is known about Andrews’ past, but in the fall of 1861 he began smuggling quinine into the Confederacy and learning information he could take back to the Union. Andrews approached Brigadier General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel commanding the 3rd Division under Buell; Mitchel’s division was left at Shelbyville while the rest of the army marched west to Shiloh. On April 2, 1862 Andrews met with Mitchel and proposed an assault on the railroad lines in north Georgia that connected to Chattanooga. Chattanooga connected the South to Richmond; there was a rail line that went straight from Chattanooga to Richmond through Knoxville and the Cumberland Gap and, in the other direction, two lines connected Chattanooga to Alabama, Atlanta, and Memphis. If the Union could take control of Chattanooga, they could cut off the west from the east and prevent men and supplies from the western Confederate states from reaching Richmond.

This was not the first time Andrews had attempted a behind-the-lines action against southern railroads. With Buell’s permission, Andrews had led eight men down to Atlanta in March to meet with a traitor railroad engineer with plans to hijack a southern locomotive. Unfortunately, this first endeavor ended in failure: poor weather and planning made plans go awry, and the engineer did not show up at their rendezvous. Undaunted, Andrews spent a few days studying train schedules and gathering information for a second try.

The plan Andrews proposed to Mitchel was daring. Sneak south almost as far as Atlanta, seize a southern locomotive, and ride north along the Western & Atlantic Railroad towards Chattanooga. Their route crossed seventeen bridges and the plan was to burn bridges north of the Etowah River, destroy as much track as possible, and cut telegraph lines. Once he reached Chattanooga, Andrews would transfer to the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad and then the Memphis & Charleston Railroad to meet up with Mitchel’s forces who would advance and capture Chattanooga. Andrews had his plan mapped out, but he needed soldiers and funds to carry it out. His original group of men were not keen to attempt it a second time, so he asked Mitchel for twenty-four soldiers to provide the needed manpower.

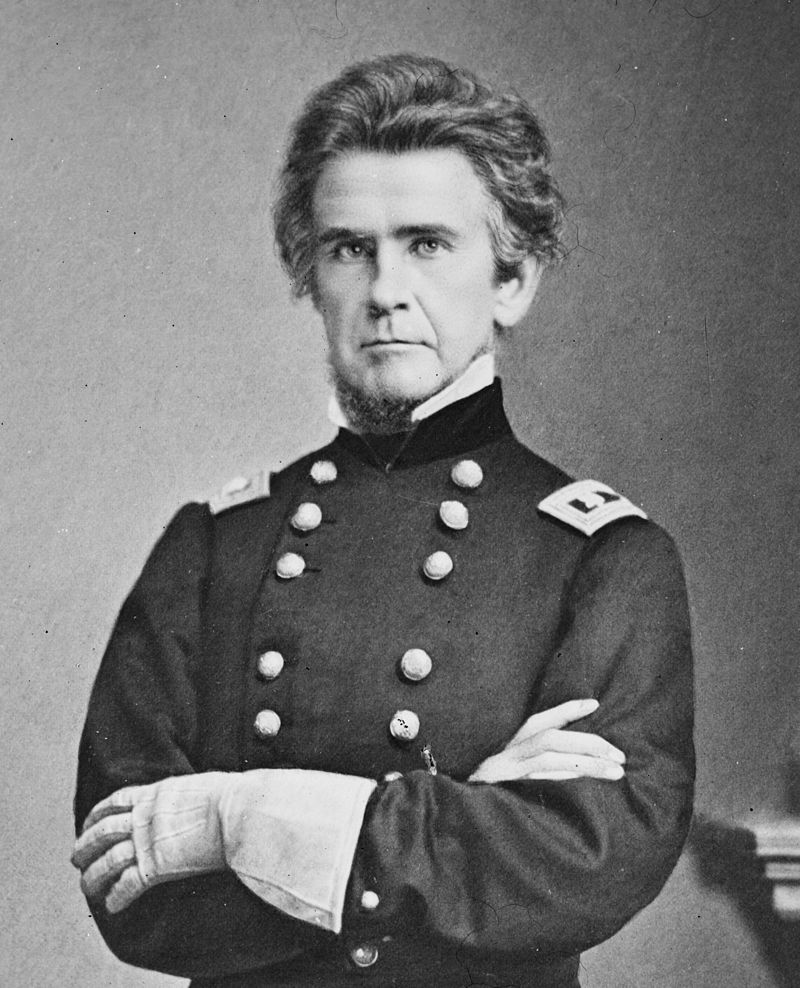

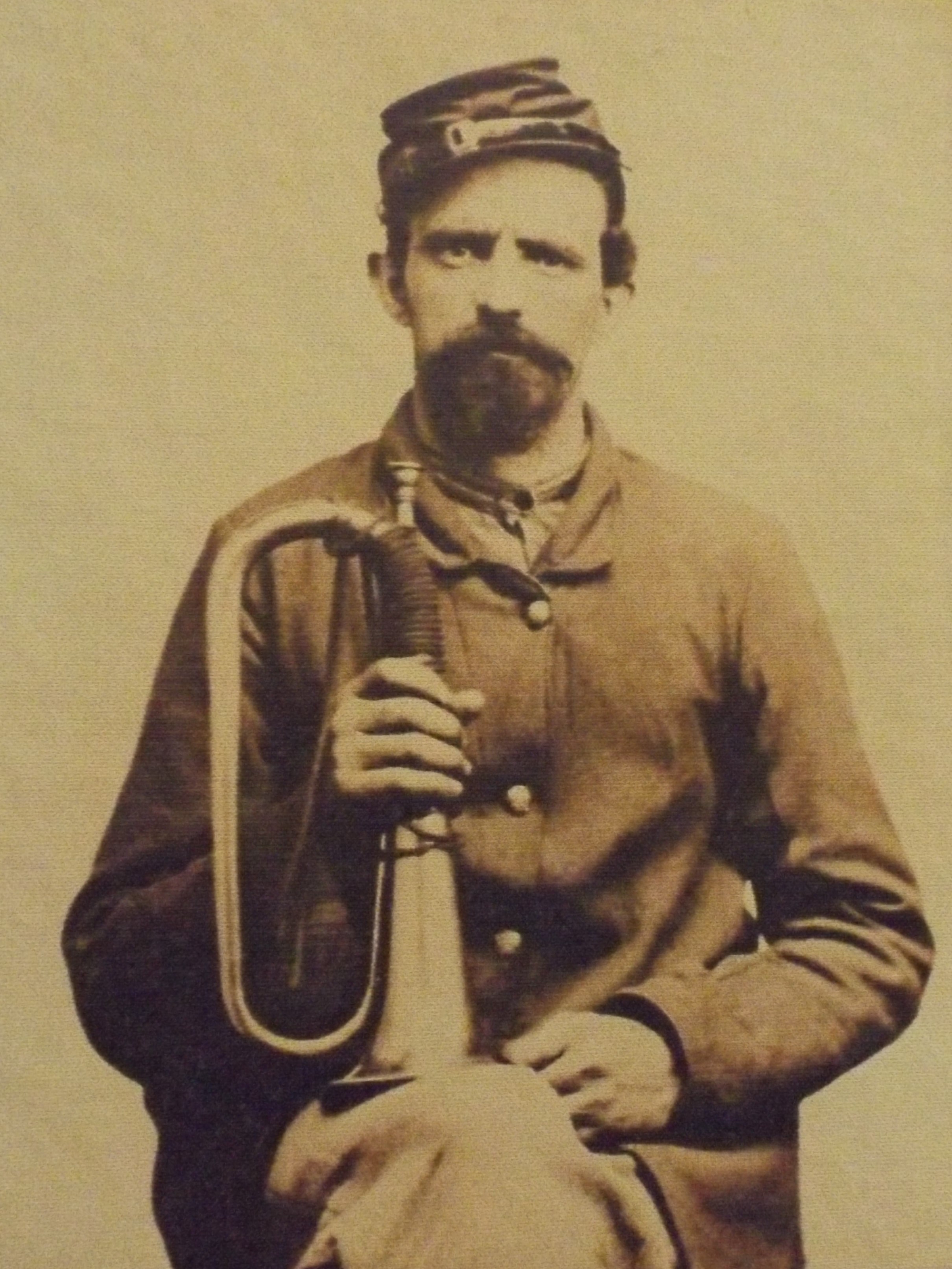

Mitchel agreed to Andrews’ plan and gave him some money to buy civilian clothing and supplies for his men. He decided to pull men from Colonel Joshua W. Sill’s brigade and directed captains to hand-pick men from the 2nd, 21st, and 33rd Ohio regiments. Andrews asked specifically for a few soldiers who could handle a locomotive, remembering the issues he had the last time in relying on an outside engineer. Three men were picked specifically as a result: Private William Knight, Corporal Martin Jones Hawkins, and Private Wilson Brown all had experience on railroads.

The group that would be immortalized as Andrews’ Raiders met for the first time on the night of April 7, 1862. Andrews instructed these men to travel in small groups to Chattanooga in the next three days where they would all board a train to Marietta, GA. Once there Andrews would meet up with them, having traveled separately, and they would spend that night in a hotel to commence their plans the following morning. If all went well, Mitchel’s Division would also be on the move in support. Their fall back plan in case of trouble was to act as Confederate civilians traveling to enlist, enlist in a nearby Confederate unit, and then find a way to escape back to Union lines. This was actually put into action very quickly; two raiders—Llewellyn and Smith—were questioned heavily on the way to Chattanooga and had to enlist in a Confederate artillery unit near Chattanooga to avoid detection.

On April 11th the raiders—minus the two already waylaid—met in Chattanooga and took the 5:00 PM train to Marietta. It was a seven-hour ride, passing the station where they would make their move the next morning, and they arrived in Marietta around midnight. Meanwhile, Mitchel’s Division moved as promised and captured Huntsville, Alabama on the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, moving closer to Chattanooga.

The plan was set to begin on April 12th…

Read the rest of the series here.

Further Reading:

Bonds, Russell S. Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC, 2007.

Pittenger, William. Daring and Suffering: A History of the Andrew Railroad Rail. Cumberland Publishing House, 1999.

Rottman, Gordan L. The Great Locomotive Chase: The Andrews' Raid, 1862. New York: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 2009.

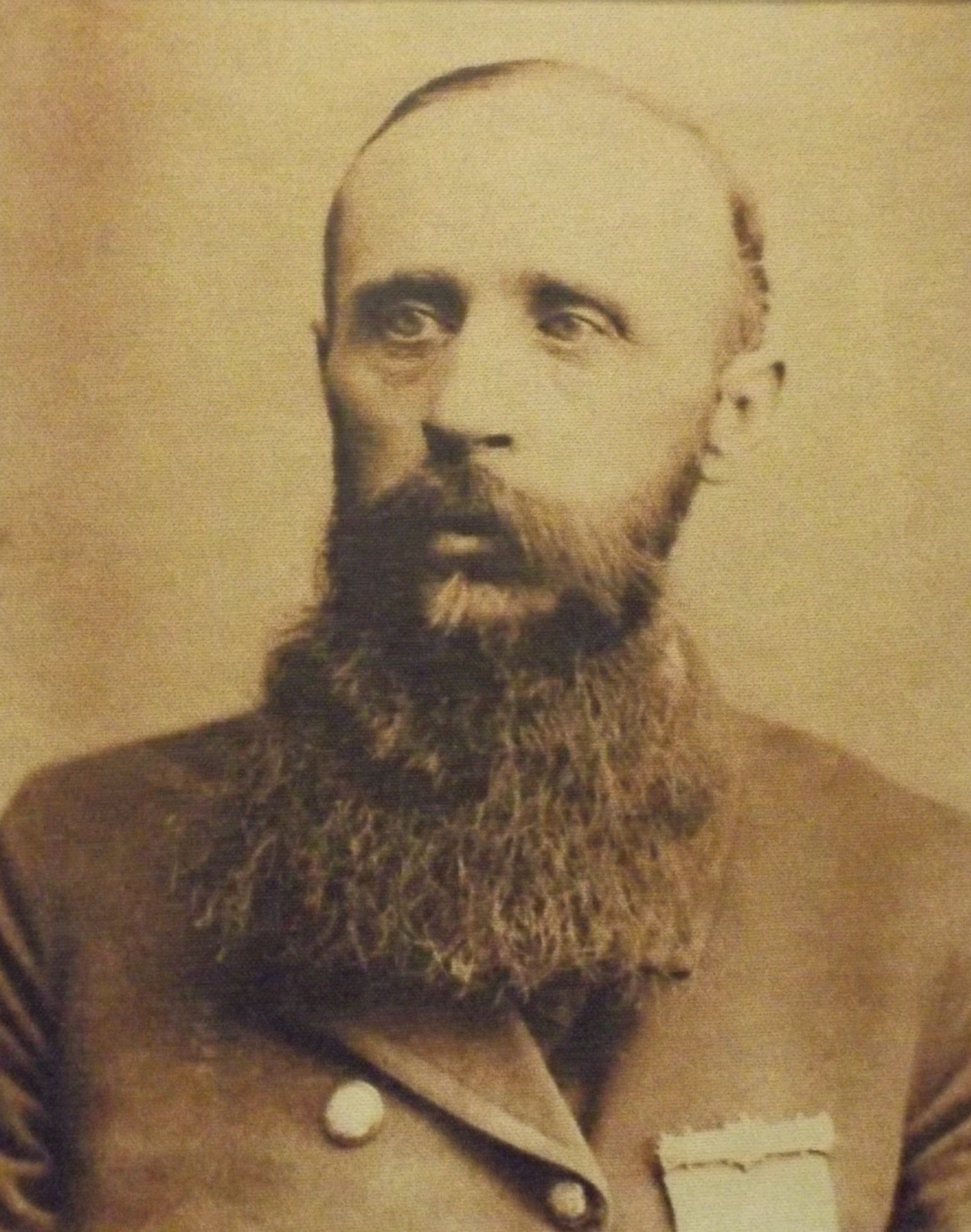

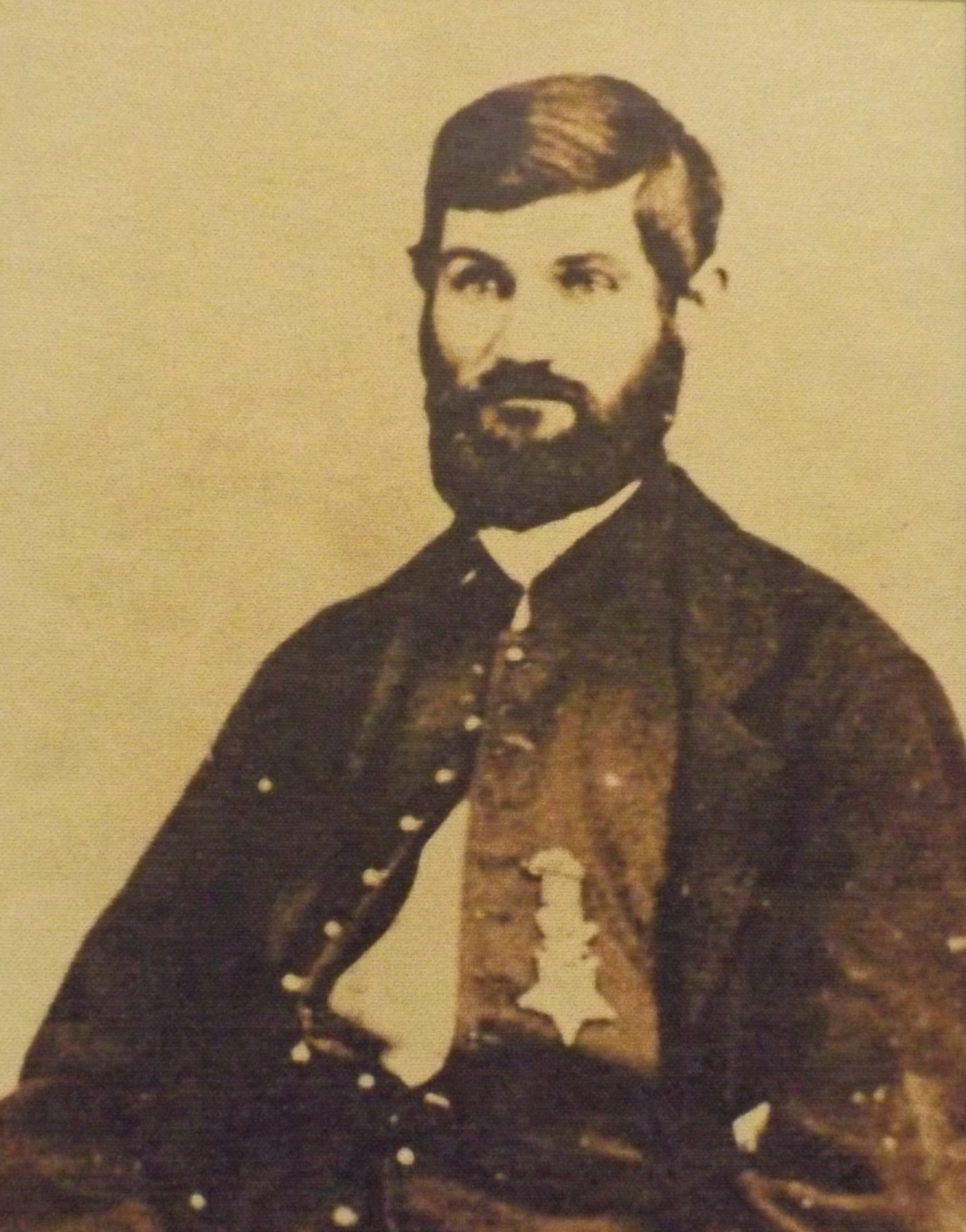

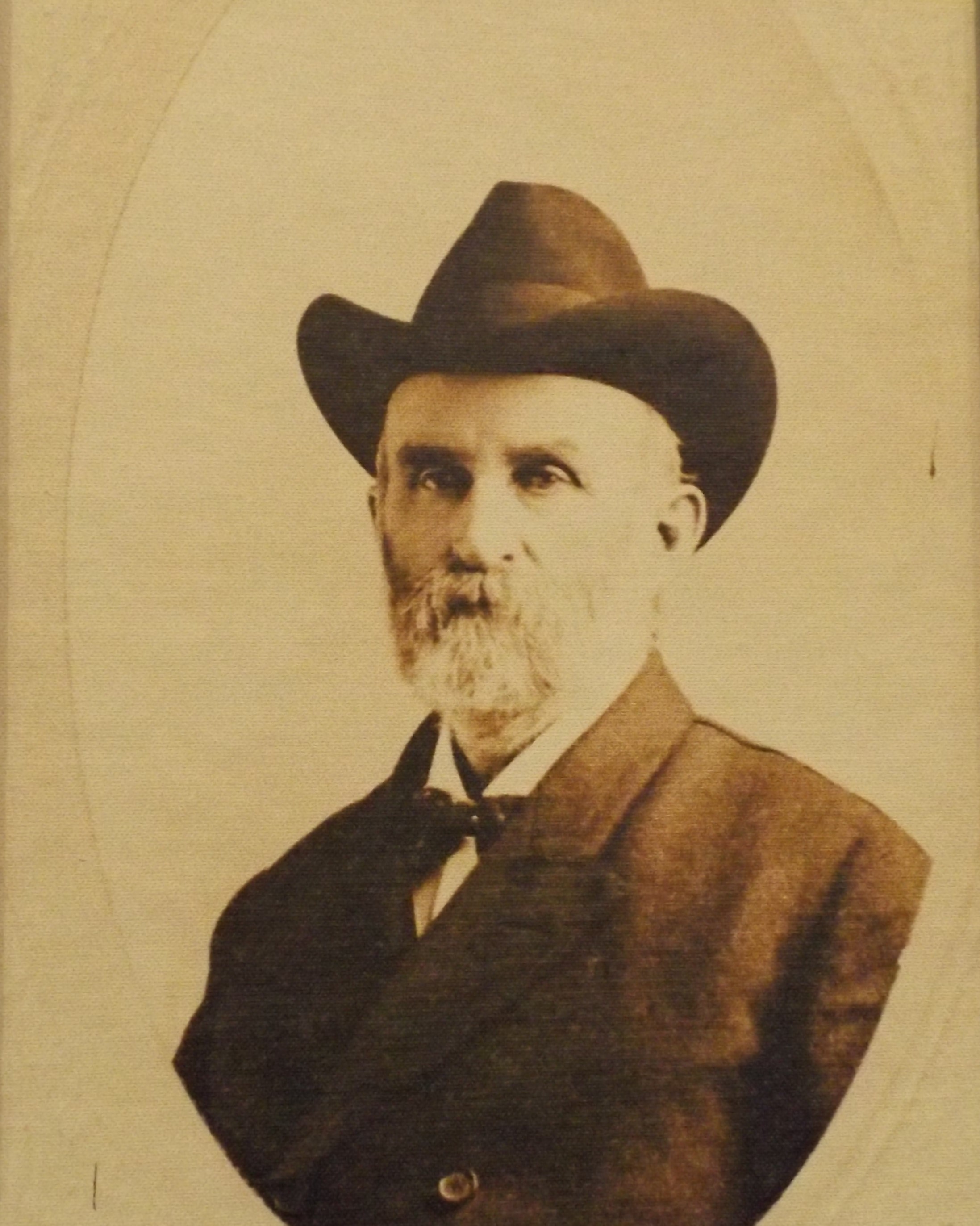

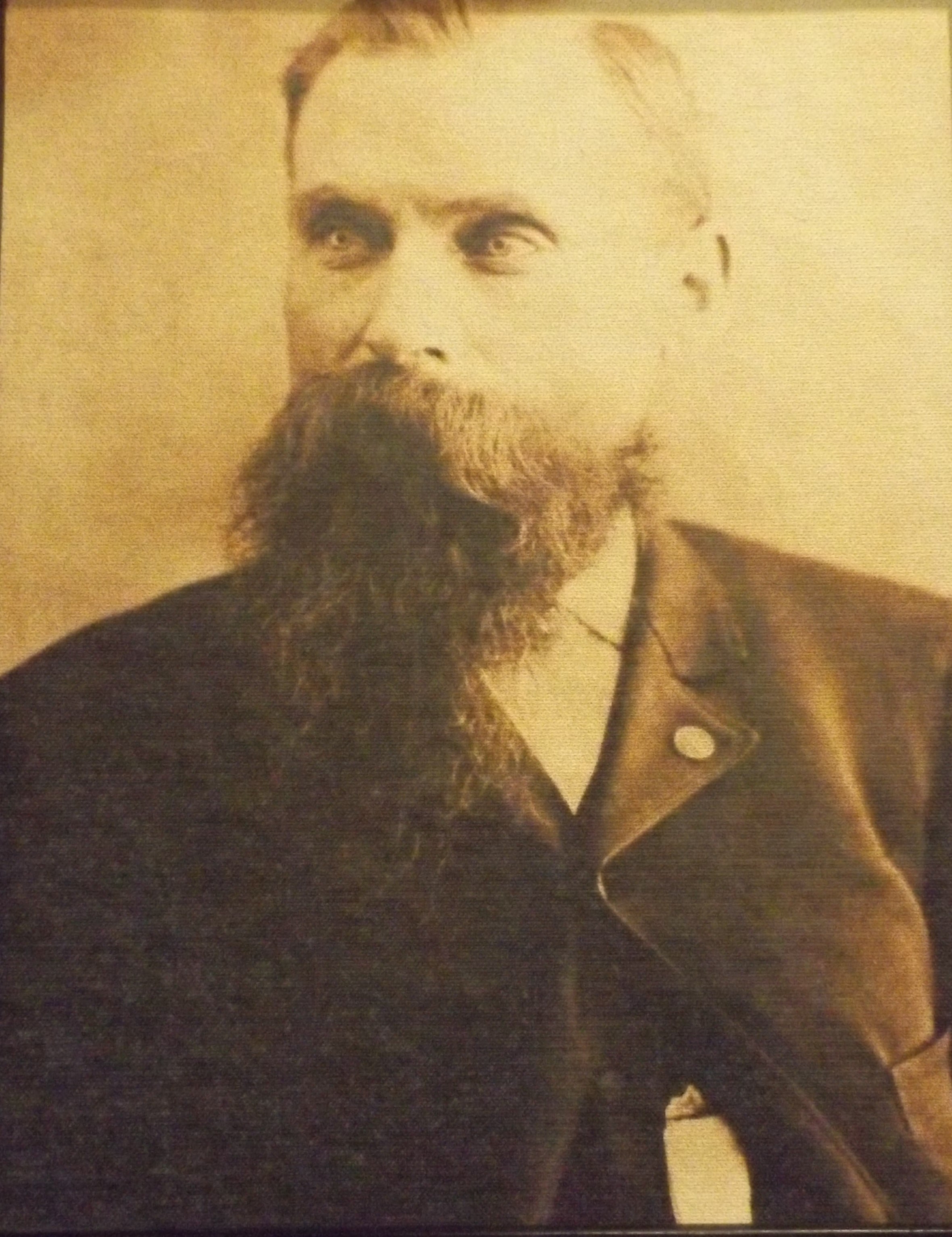

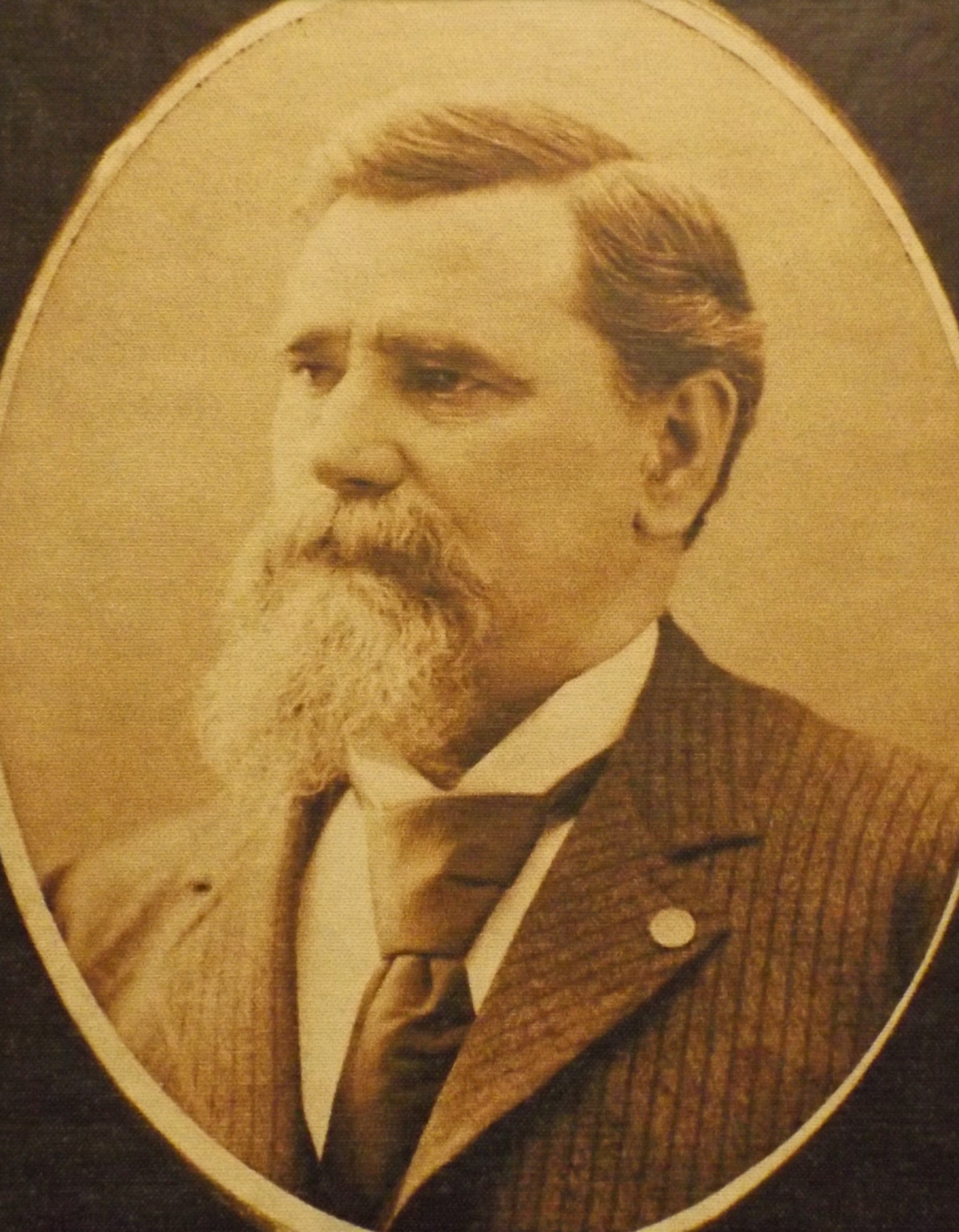

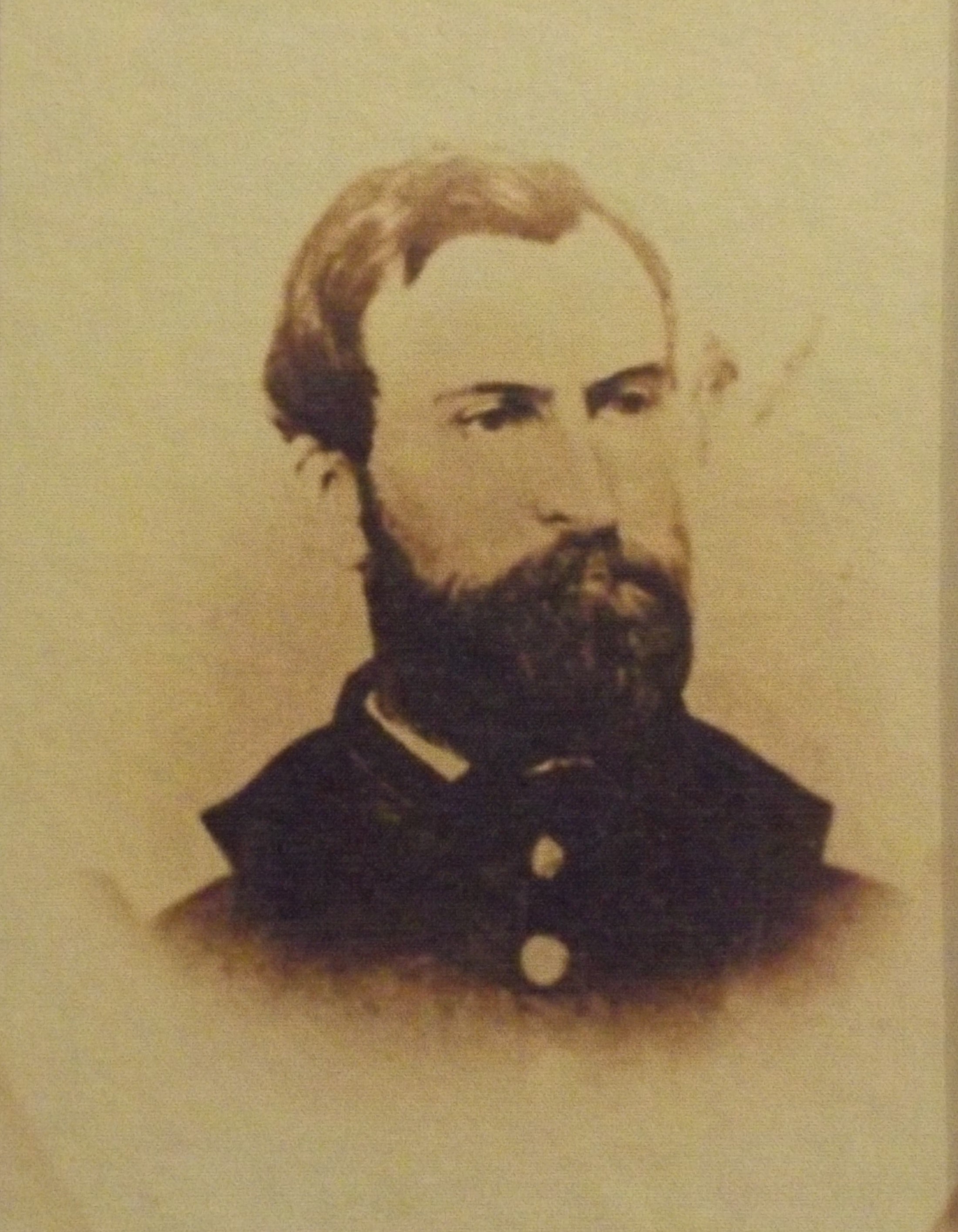

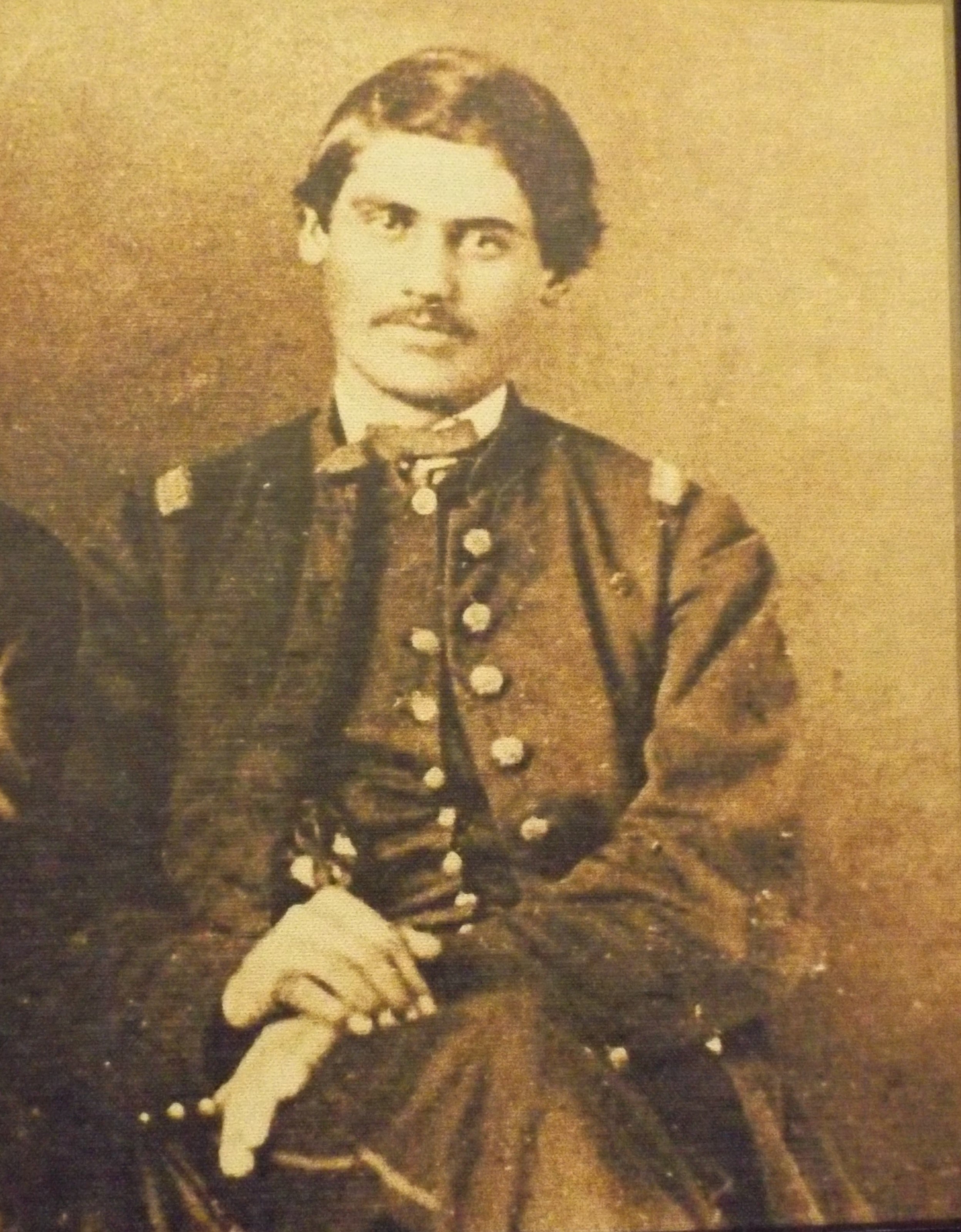

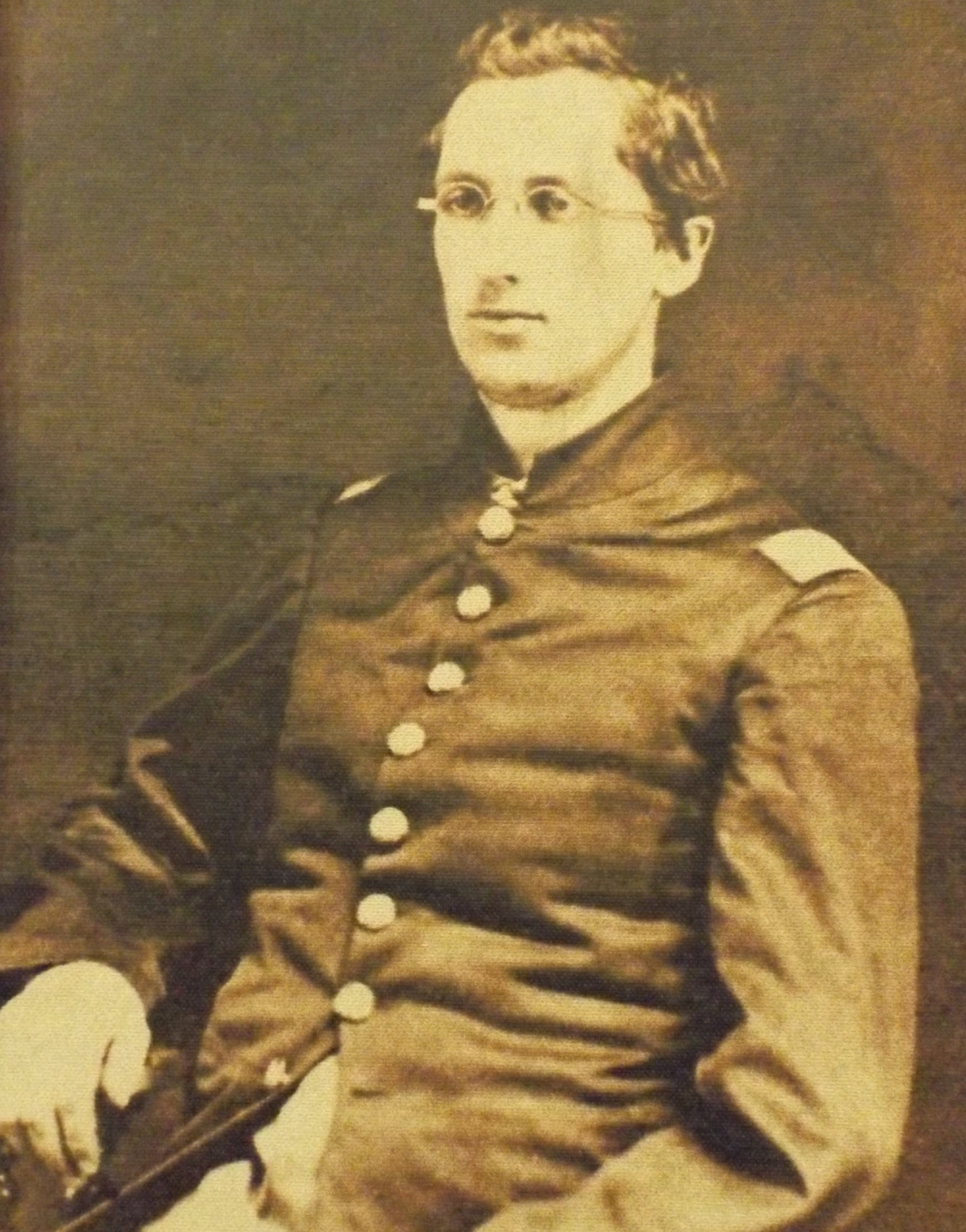

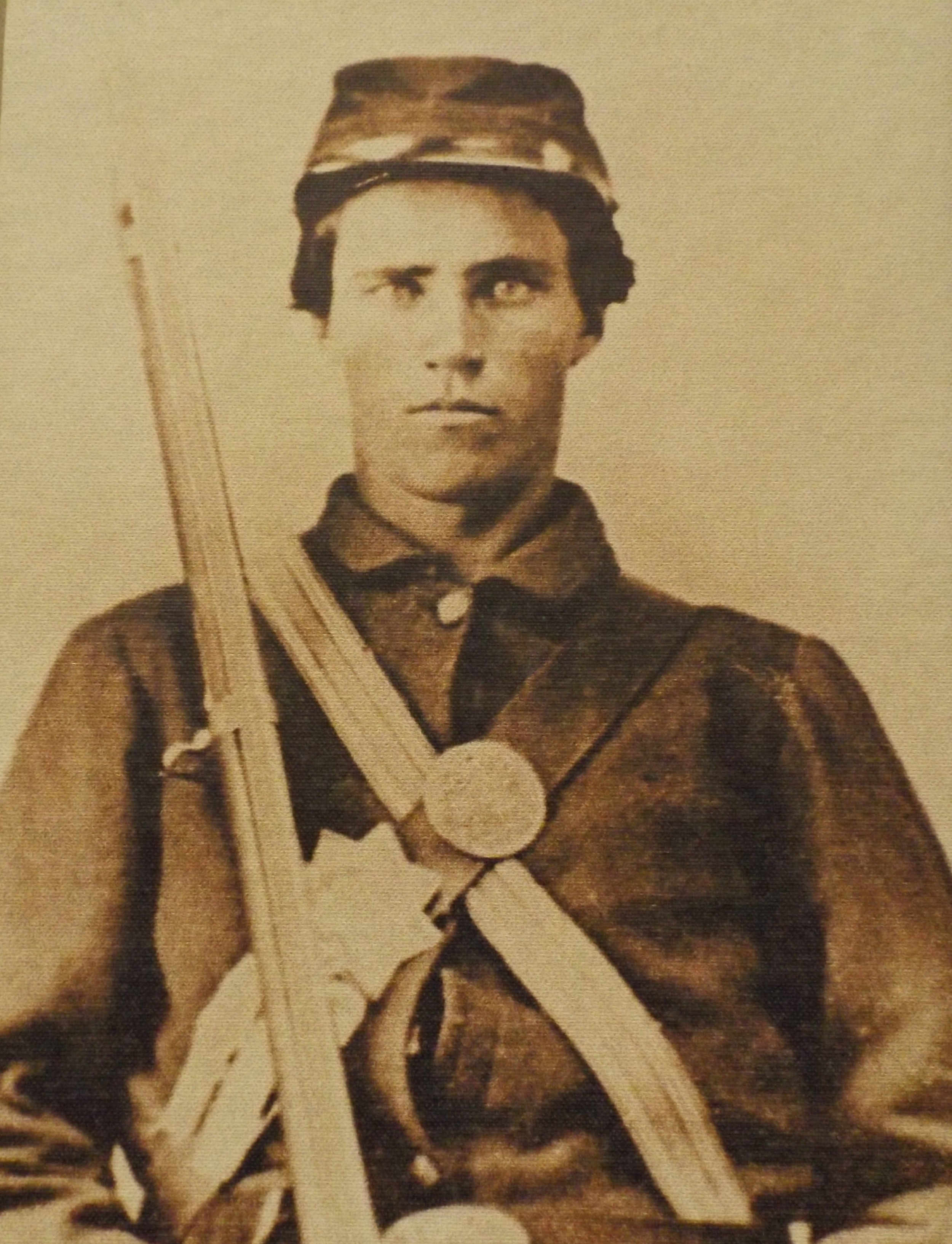

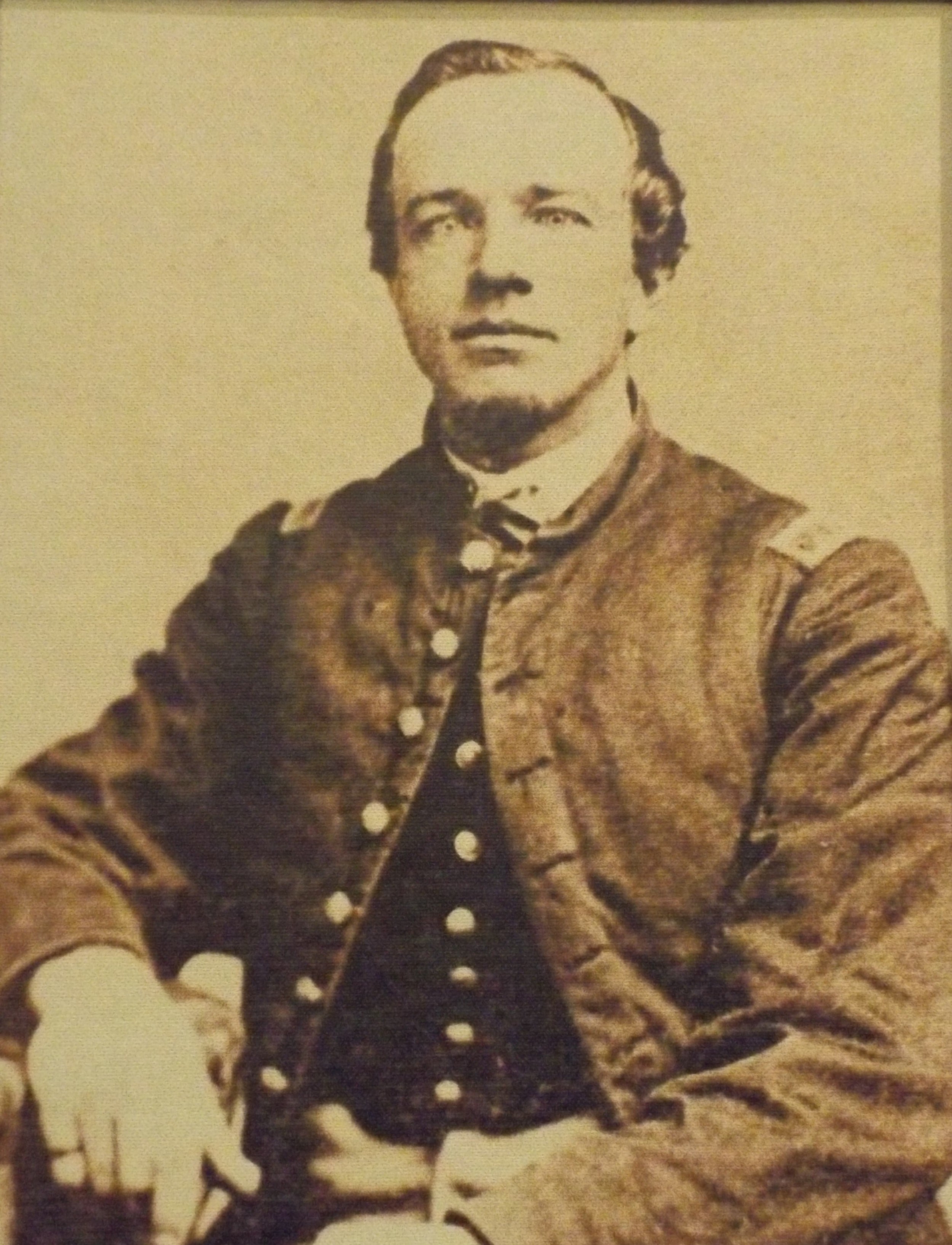

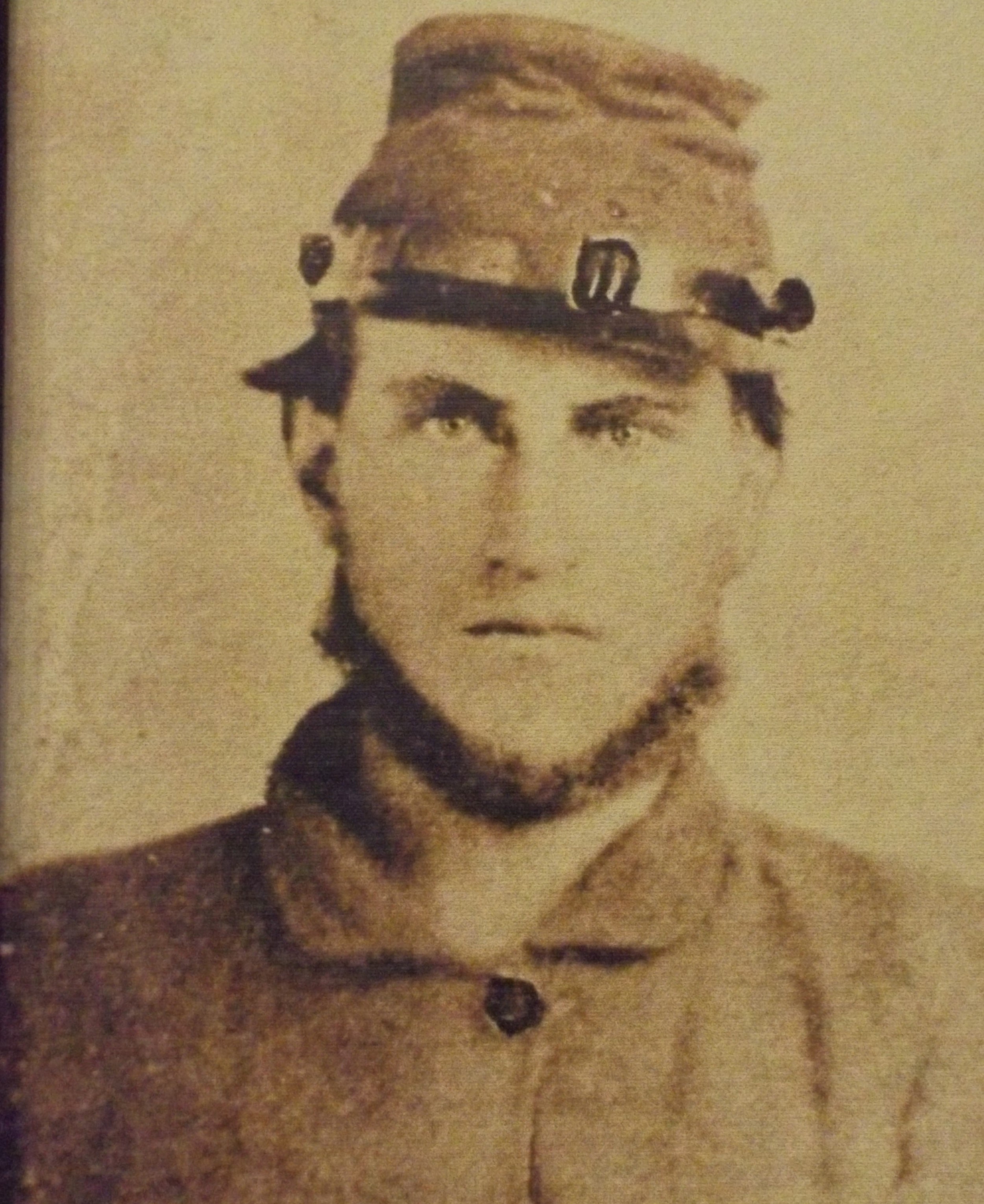

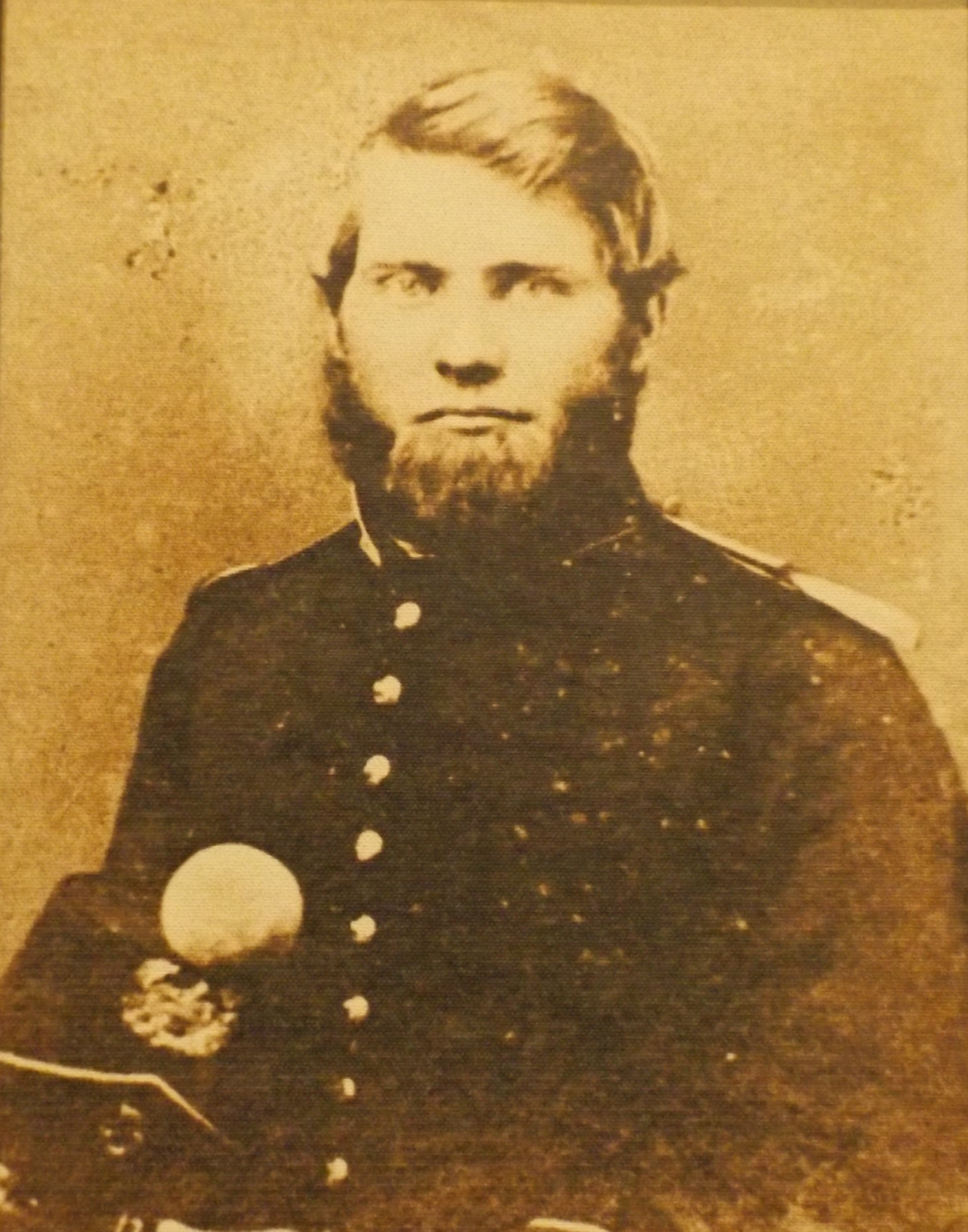

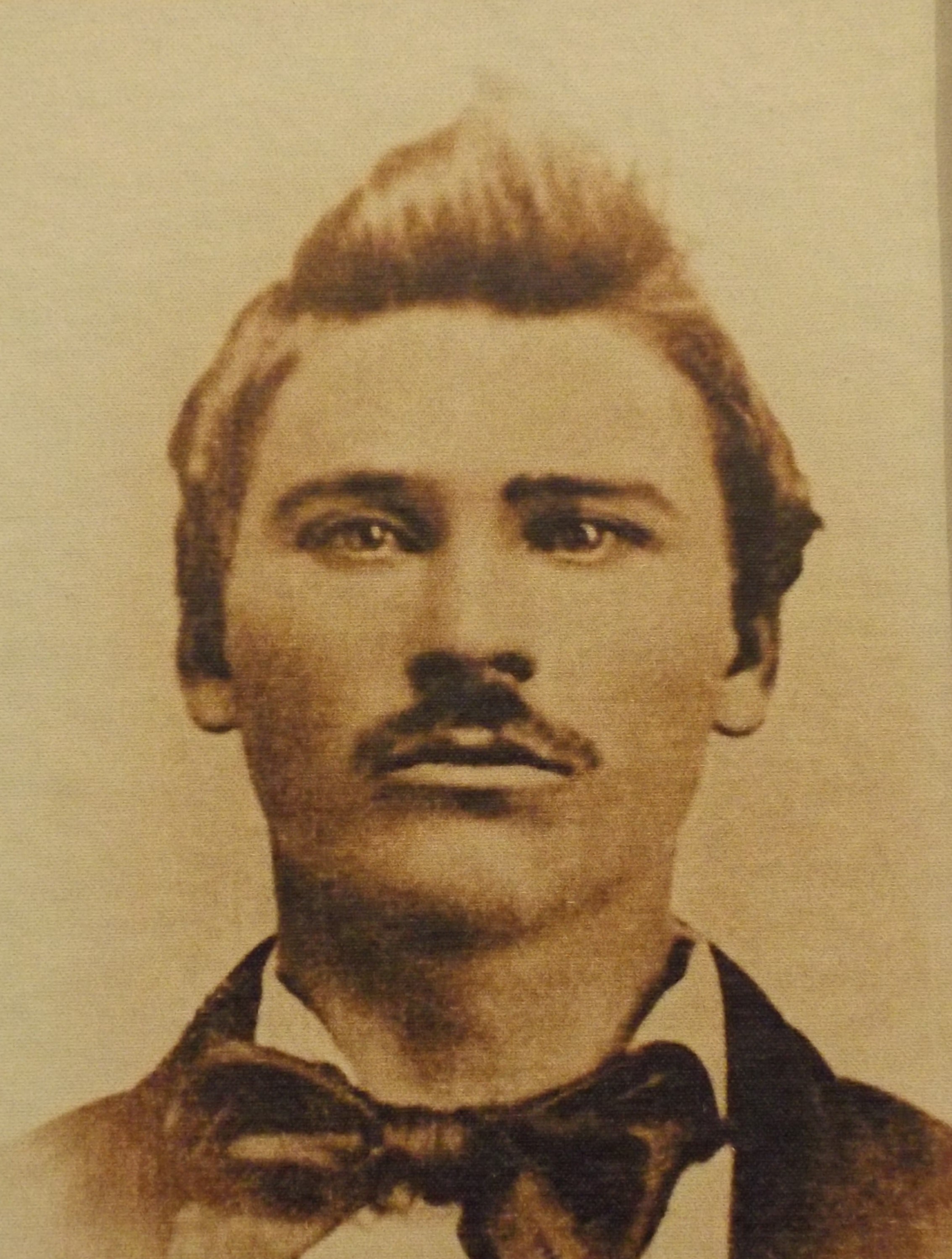

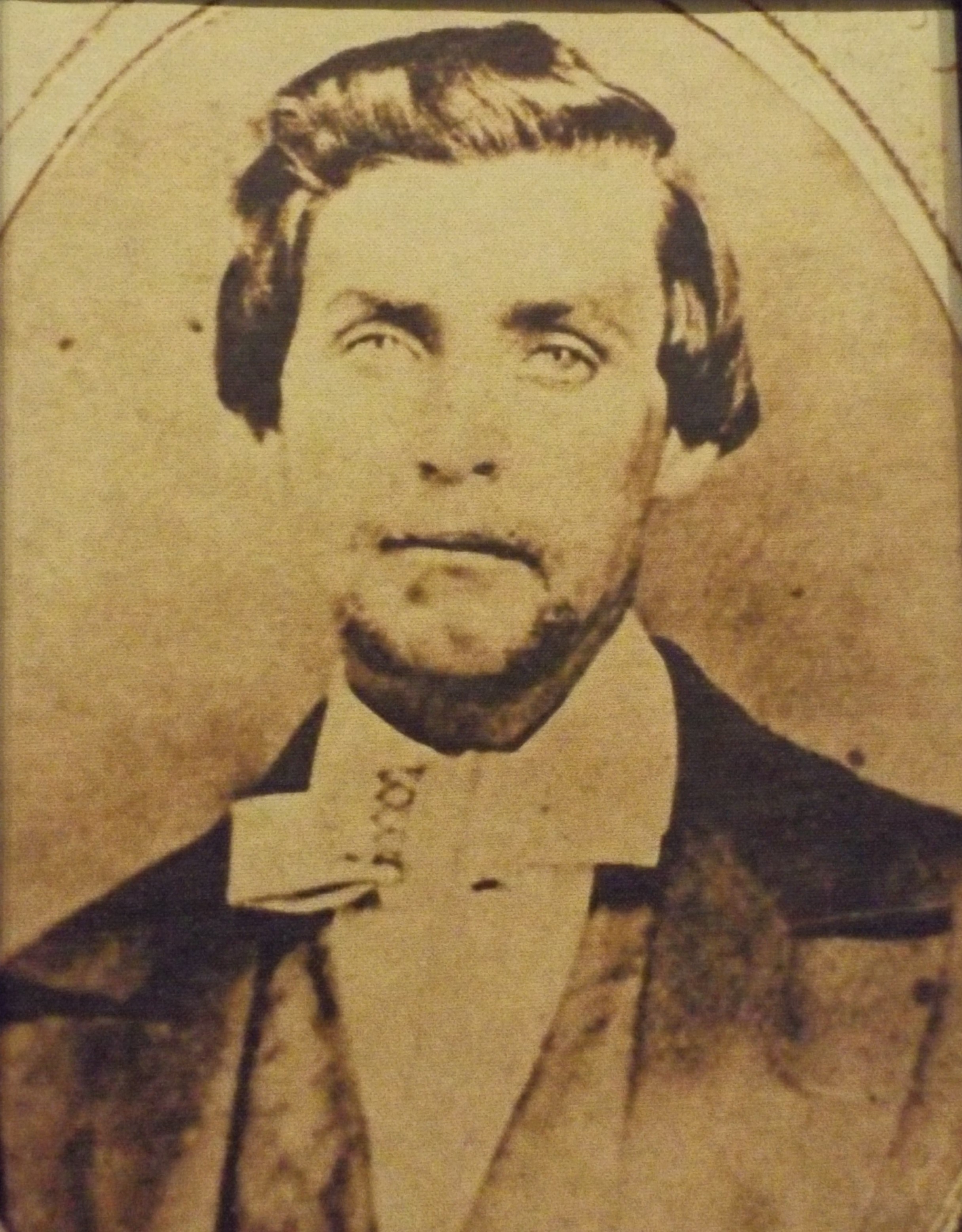

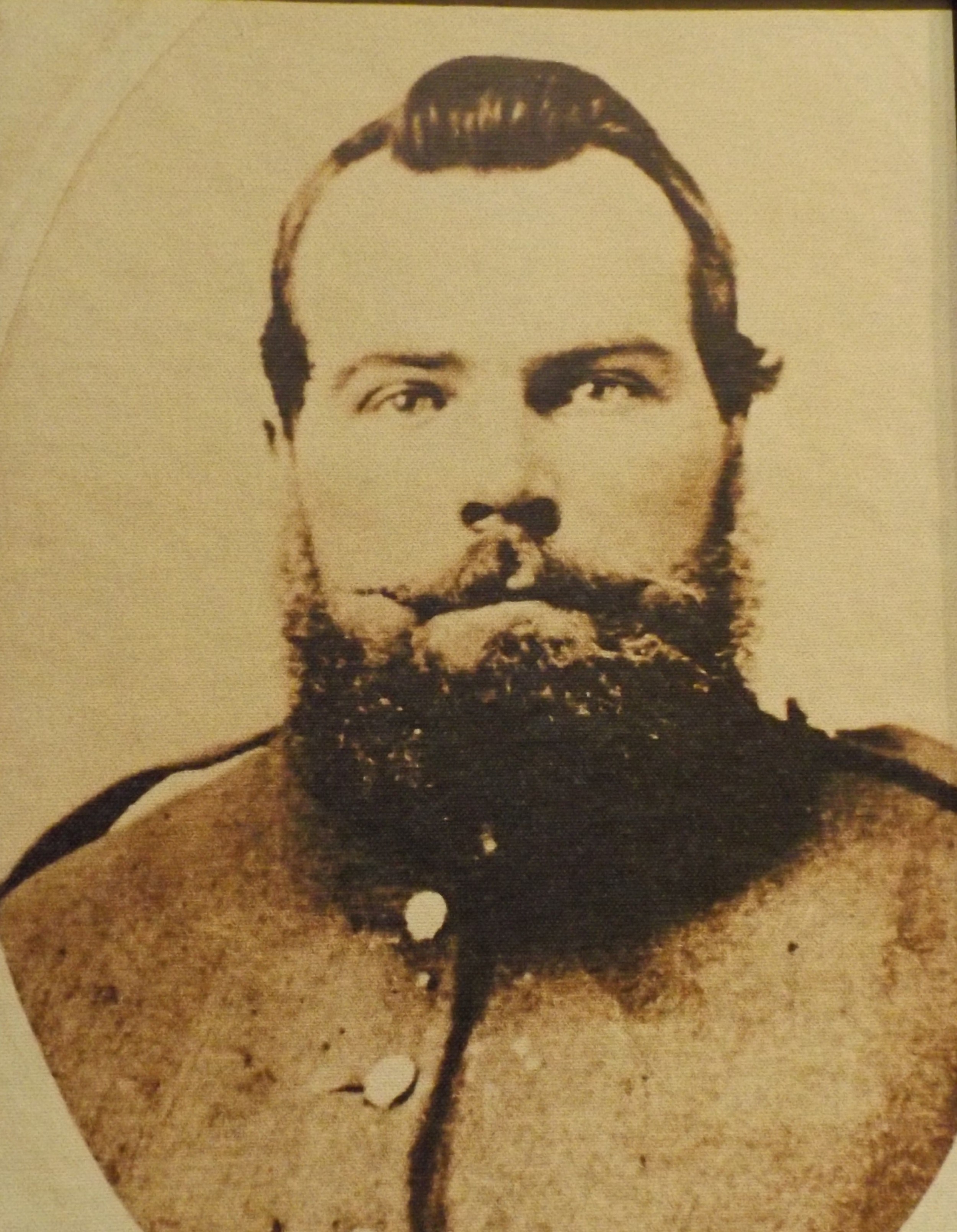

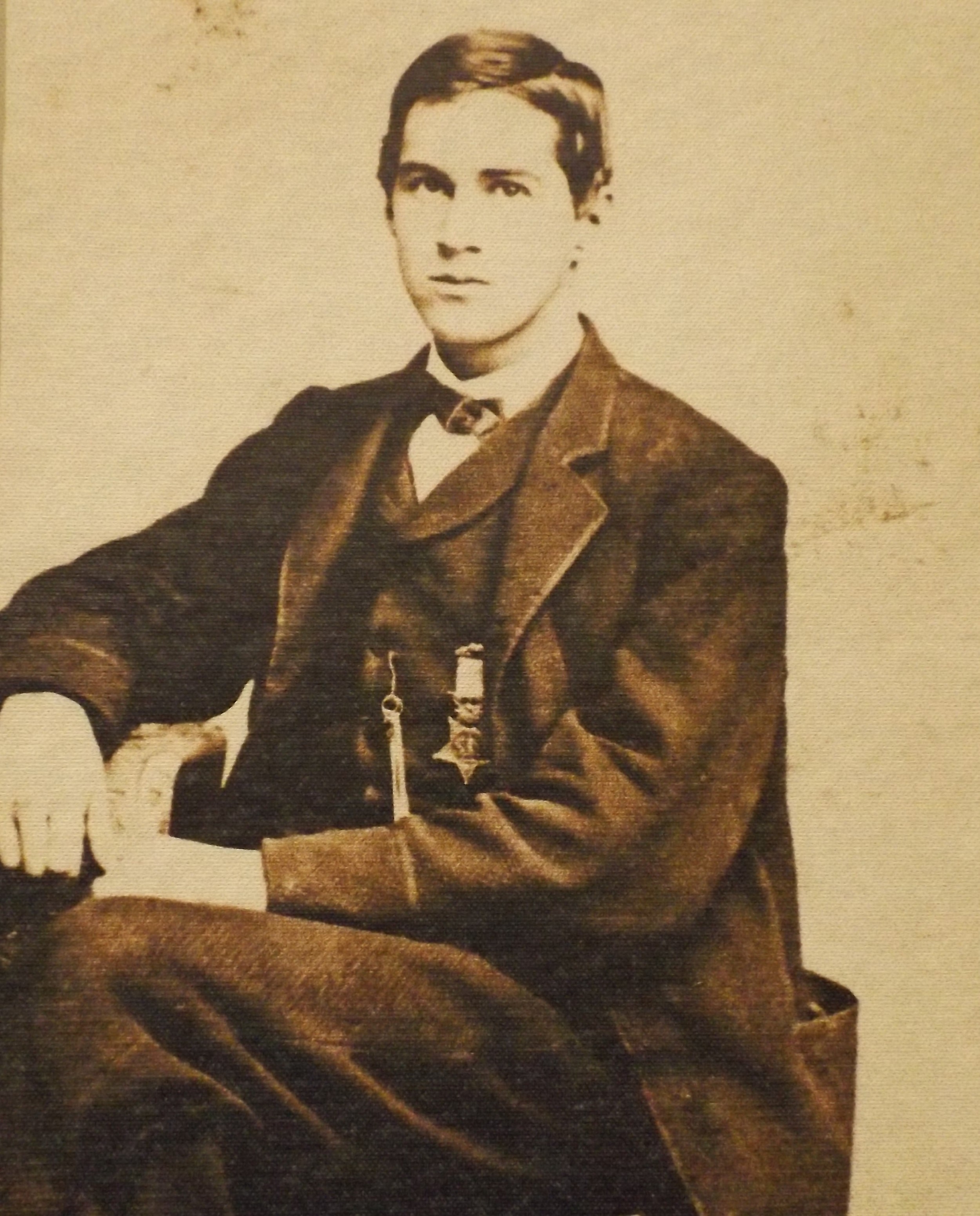

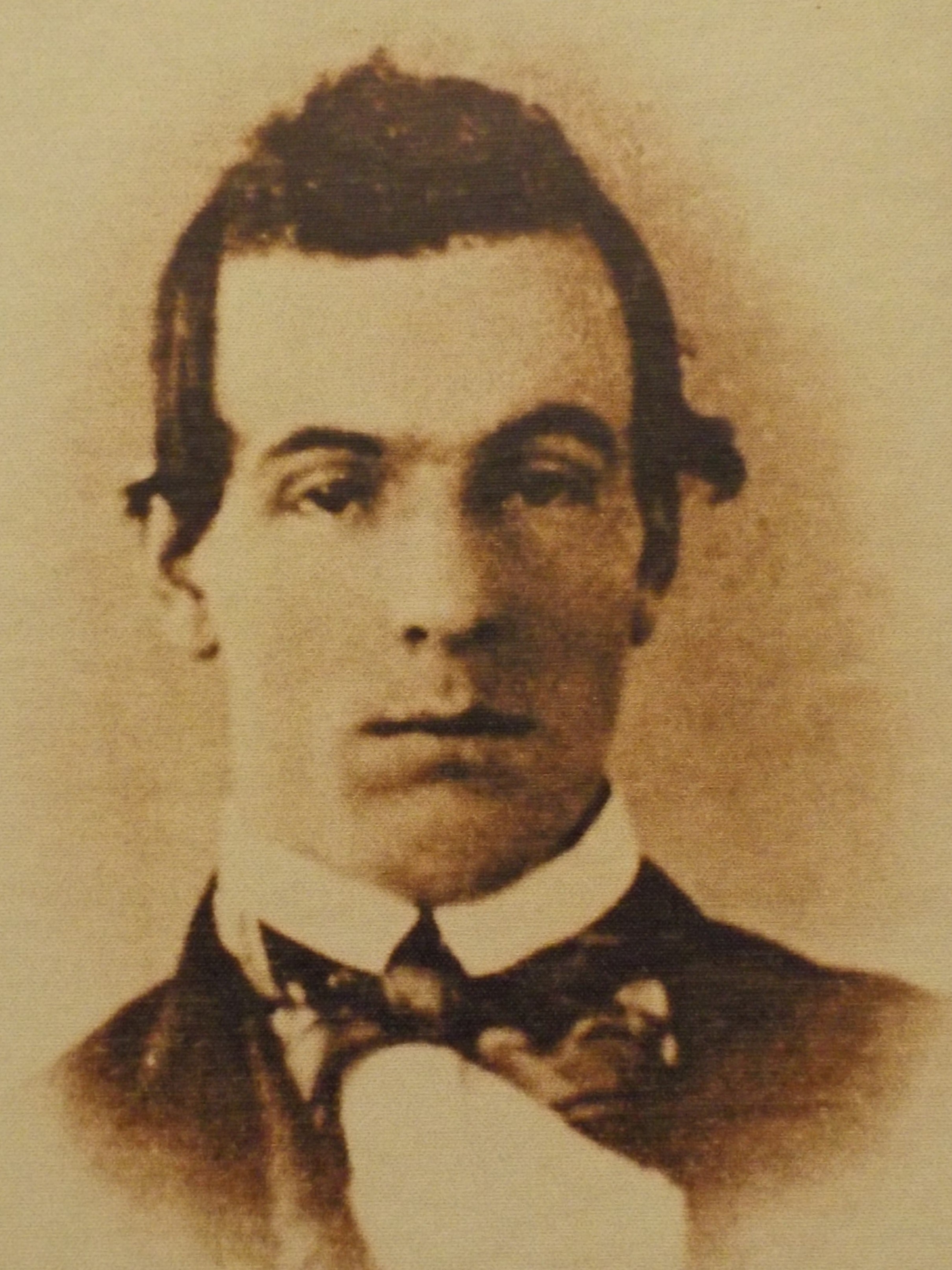

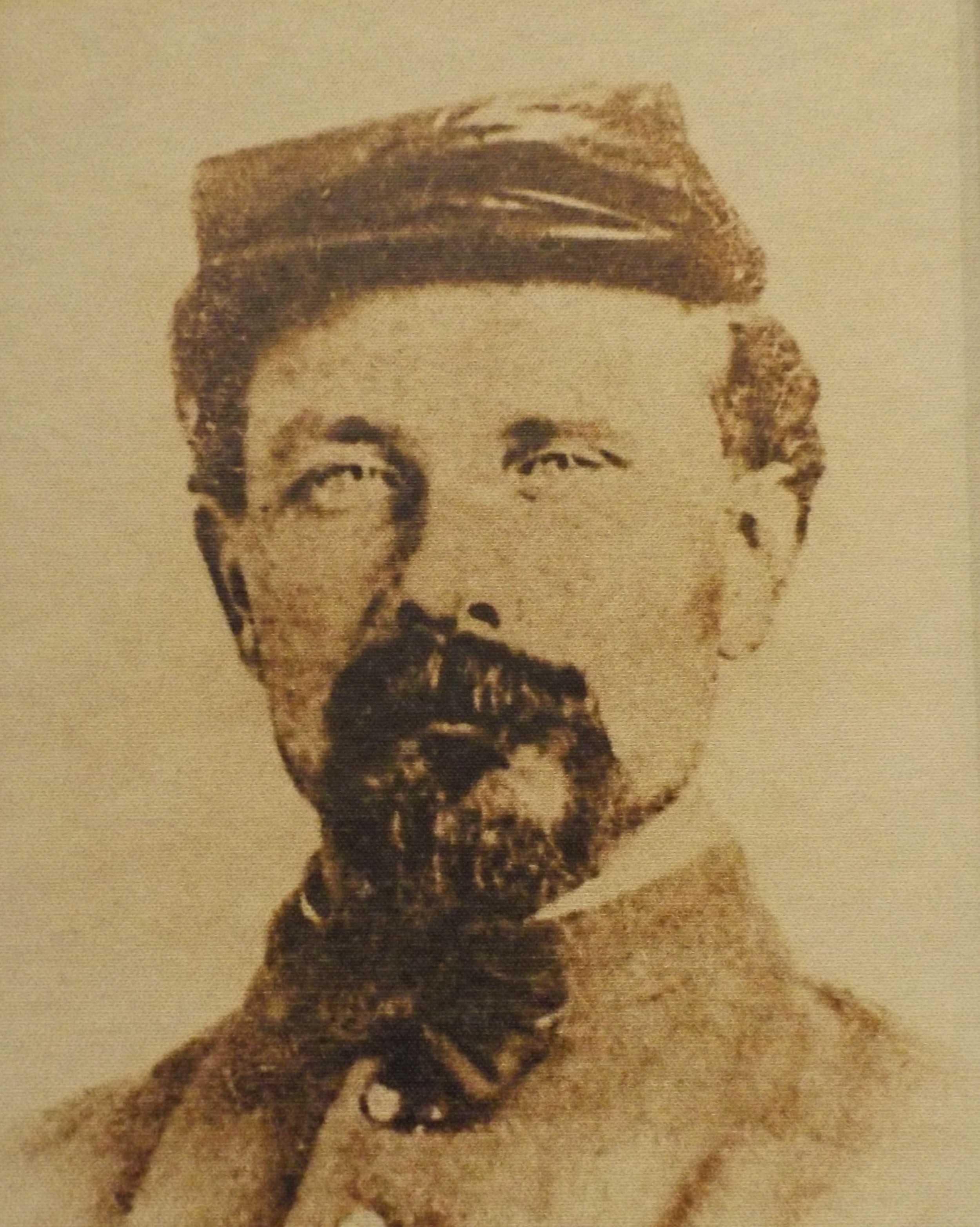

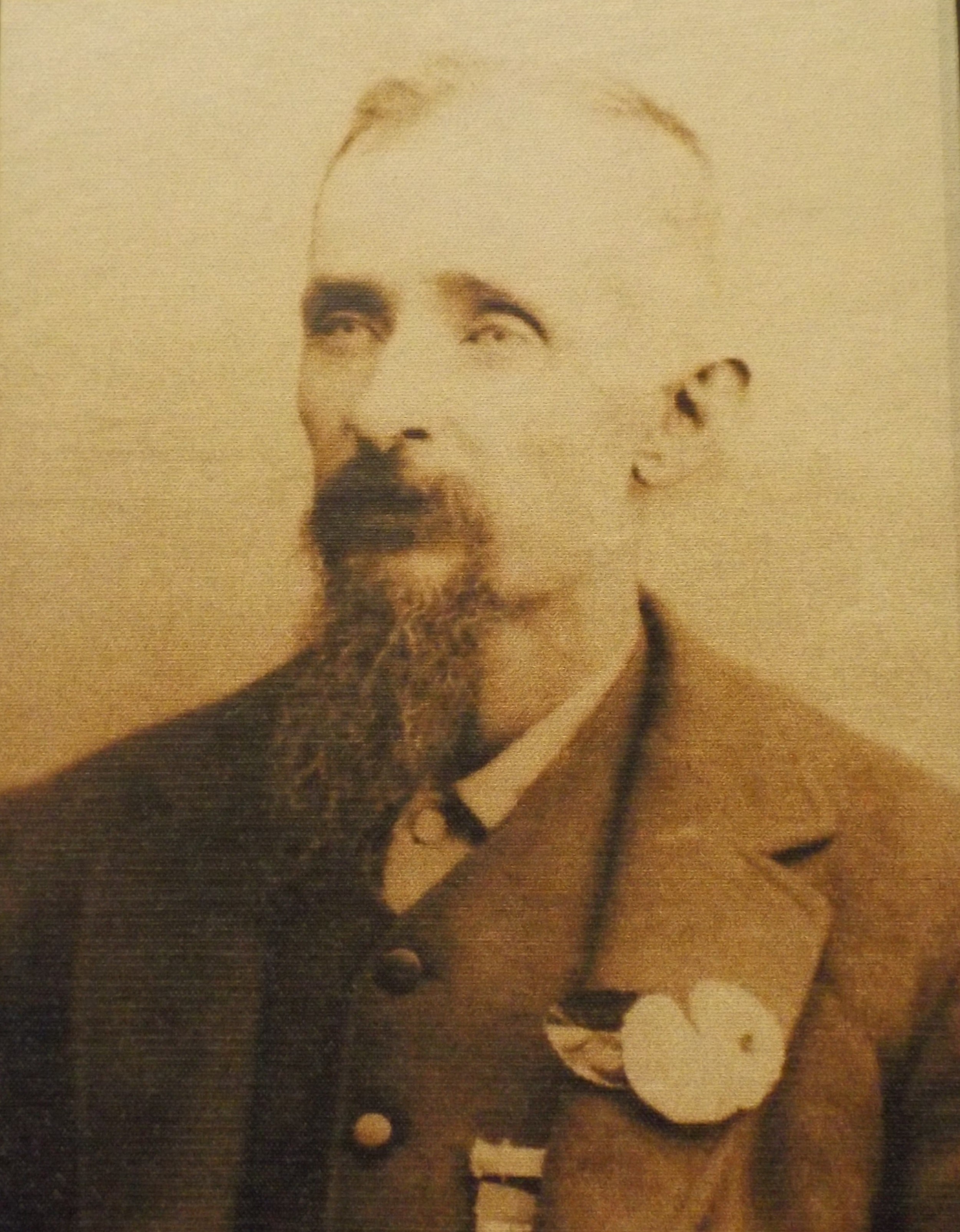

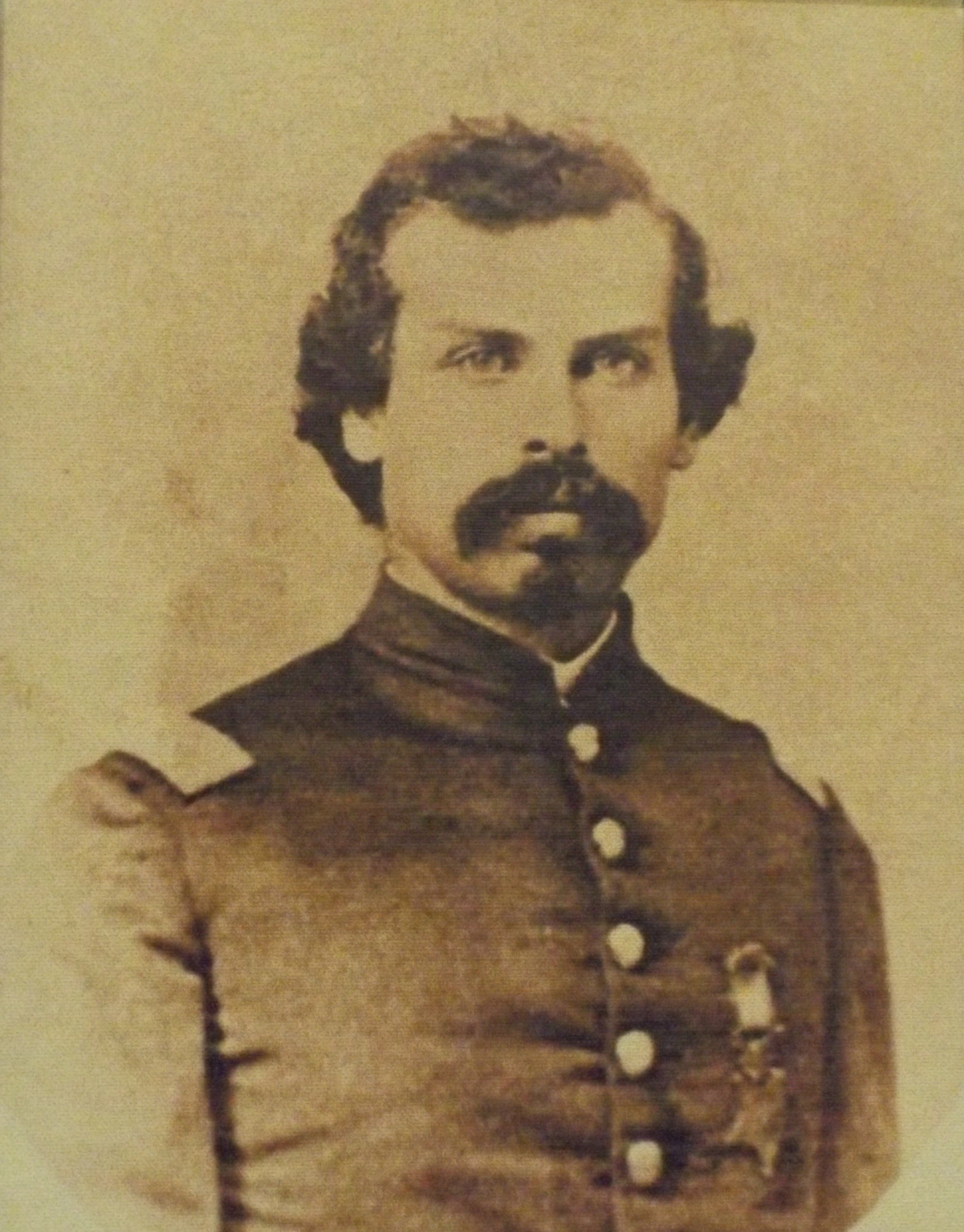

The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in Kennesaw, GA has an extensive exhibit on the Andrews' Raid, including the restored General (above photos of the raiders are from this exhibit).

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen was a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park from 2010-2014 and has worked on various other publications and projects.