Confederate Meccas: The Unexpected Legacy of the Civil War in East Tennessee

/Spend any length of time in East Tennessee and you will be inundated with Confederate battle flags. They come in every shape, size, or medium you can imagine - from bikinis to shot glasses and everything (and I mean everything) in between. Perhaps more unsettling, you would also witness a strange phenomenon of cars and trucks sporting battle flags creating an impromptu parade through the streets, driving aimlessly and making some sort of statement, though it is unclear how menacing that statement might be. It happens almost nightly.

A portion of one such parade of Confederate battle flags in East Tennessee.

The Confederate flag represents a variety of different interpretations of the Civil War. A constant media barrage of conflicts over these contested meanings leaves little room for debate that the flag itself resists being defined in a single, particular way. But when it comes to big-picture type themes like the causes of the Civil War or what the Confederate flag stands for, I find it is extremely useful to look at microhistory for a more concrete understanding. On some level, this means we take a distorted view - one place does not speak for all. However, on the other hand, it complicates our understanding and forces us to reckon with the reality that history is complex and a single explanation does not resolve the tension we continue to experience today.

So what is the legacy of the Civil War in East Tennessee?

The short answer is, not a good one.

War came to East Tennessee in the form of guerilla conflicts that harassed the lesser-developed portions of the United States in 1861. The area known as the Smoky Mountains was a hostile environment in which to attempt to survive, and its population reflected that fact. Small towns had emerged in the mountains, but the communities primarily consisted of farmers who grew just enough to provide for their families. Consequently, slavery was scarce compared to other sections of Tennessee and its neighboring states of Virginia and North Carolina.

Perhaps surprisingly to modern visitors, East Tennessee was in fact a Unionist stronghold, home to many who had no desire to join the quickly emerging slavocracy of the South. Prior to the outbreak of war, William Brownlow, a resident and editor of the Knoxville Whig vehemently declared that East Tennesseans would, “never live in a Southern Confederacy and be made the hewers of wood and drawers of water for a set of aristocrats and overbearing tyrants.” Confederate Major General Edmund Kirby Smith, lamented in 1862, “No one can conceive the actual condition of East Tennessee, disloyal to its core, it is. . . an enemy’s country, its people beyond the influence and control of our troops and in open rebellion.” This resistance to Confederate control, and disdain for any neighbors who joined the Southern cause, would bring the wrath of Confederate troops and sympathizers down on Tennessee loyalists for the duration of the war.

Recent scholarship has revealed that mountain territories in border states during the Civil War witnessed a particularly brutal type of conflict. The treacherous terrain made such areas appealing places for draft dodgers, deserters, and general malcontents from both sides. Lawless bands of men roamed freely, taking advantage of local populations as they went. To say East Tennessee’s version of this conflict was vicious would be a gross understatement. Secessionists wrecked havoc on the loyal communities of the Smokies, murdering, raping, and torturing residents. Many families fled into the mountains for safety.

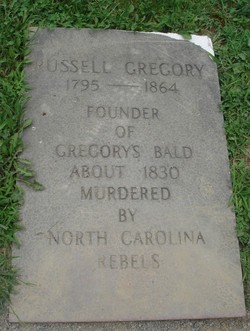

Some communities, like Cade’s Cove, attempted to establish warning and defense systems against these marauders. Situated in a valley, residents of the Cove posted lookouts on the mountaintops who could warn others if bands of men started to approach. Russell Gregory, pastor of the Primitive Baptist Church, closed his doors and organized fellow loyalists into a home guard. Gregory’s initial success at protecting his home would ultimately cost him his life; he was murdered in his home by Confederate raiders in 1864.

The particulars of the atrocities committed by Confederate sympathizers against loyalists in East Tennessee are nothing short of sickening. It was a type of cold-blooded violence that is almost entirely absent from the majority of Civil War scholarship. Yet it was a grim reality for a population struggling to survive, and as more and more scholarship has revealed, not unique to a single area. Many of the families who inhabited East Tennessee in the late 19th century still reside in there, and the reality of their ancestors’ suffering must give you pause when confronted with a parade of Confederate flags invading their home today.

The Confederate flag may mean many things, but for this particular place it speaks to a legacy of vicious violence and inhuman acts. Certainly, these acts were not necessarily condoned by the Confederate government, but they were perpetrated by groups attempting to support the Confederacy and representing a particular type of Confederate sympathizer. Furthermore, the Confederate high command was aware of the violence in East Tennessee, often committed by regular troops, yet they did nothing to prevent or curtail it. To state the obvious, we must also go further and recognize that the type of systematic violence and terror that occurred in and around the Great Smoky Mountains would be used on a broad scale by unreconstructed rebels after the war’s close.

Like most things in the Smokies, Civil War history has been handed down through the generations. It is rich in oral tradition, with competing versions of the same story making an appearance now and again. Yet it is clear that the memory of the violence experienced by these communities remains strong, and some concrete reminders remain in what is now Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

So what does it mean to fly a Confederate flag in this particular place? It is clear what it does not mean, because this is not the narrative of “states’ rights” and “home defense” that many Confederate flag supporters hold dear. The people who lived here wanted to remain in the Union - but their desires were suppressed through brutality and intimidation. What then, does it mean?

Becca Capobianco is an education technician at Great Smoky Mountains National Park and an adjunct faculty member at Germanna Community College.

Sources and Additional Reading:

Ash, Stephen. Middle Tennessee Society Transformed, 1860-1870: War and Peace in the Upper South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988.

Fisher, Noel. Civil War in the Smokies. Gatlinburg: Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2005.

Fisher, Noel. War at Every Door: Partisan Politics and Guerrilla Violence in East Tennessee, 1860-1869. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2001.

Simmons, Morgan. “Story of Cade’s Cove man’s death reveals divisions during the Civil War.” http://www.knoxnews.com/news/gosmokies/splintered-relations, 2011.

Spradlin, Darwin. “Russell Gregory.” https://www.legacystories.org/public-archives/stories /entry/russell-gregory.

Sutherland, Daniel. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2013.