The Reconstruction of Billy Mahone

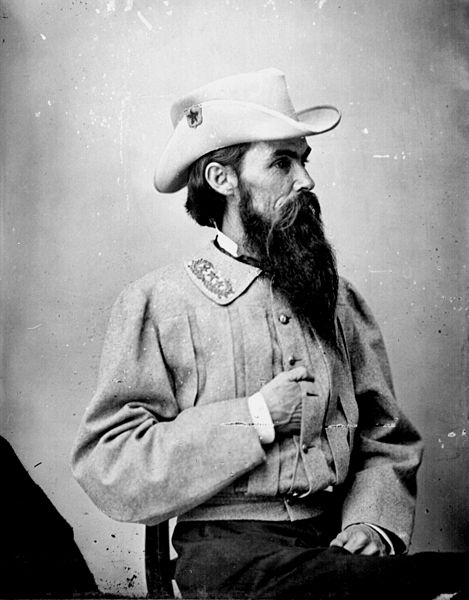

/The descriptions of him are priceless. “He looked the image of a bantam rooster or a gamecock,” recalled a veteran. Perhaps it was his odd dress: “He wore a large sombrero hat, without plume, cocked on one side, and decorated with a division badge; he had a hunting-shirt of gray…while he wore boots, his trousers cover them; those boots were as small as a woman’s.” Or perhaps he was just plain odd, “the sauciest-looking manikin imaginable” and “the oddest and daintiest little specimen.” His five-foot stature and frail 125 pound frame didn’t help.

William "Billy" Mahone was a genuine character, and his life was as unique as his stature. Although a rising star in the Army of Northern Virginia by the end of the war, his post-war political career in the darkness of Reconstruction and Redemption is perhaps his true shining moment. “Bantam” Billy Mahone revealed his character not only as a fighter on the battlefield, but as a progressive on the political stage.

So much has been written about the American Civil War that surely much of William Mahone’s contributions within that violent conflict have been covered sufficiently. Moreover, while we often focus on the war itself here at Civil Discourse, Reconstruction deserves exploration and understanding as well. The latter has always seemed especially important to me. While the Civil War enacted a many great changes and wiped the slate clean, Reconstruction determined what would then be written. So today I want to focus not on Billy Mahone's wartime exploits, but rather post-war political career and the struggles of Reconstruction Virginia.

Born in Southhampton County, Virginia in 1826, William Mahone was the son of a tavern-keeper. The tavern may have shaped Billy significantly, for by all accounts he was a wild child. Mahone was a “sandy-haired, freckled-faced little imp” who “smoked, chewed, cussed like a pirate, gambled like a Mississippi planter.” Despite his sinful impetuousness, Mahone did managed to enter the Virginia Military Institute when he was eighteen, but he predictably struggled, especially his first year. He was described as ”a youngster of precocious judgment, boundless enterprise, great ambition to win…and indomitable grit.” VMI may have educated Mahone, but it apparently did not change his free-spirited, fiery nature.

After graduating from VMI in 1847 and serving his obligatory year teaching school at Rappahannock Academy near Fredericksburg, Billy Mahone began a career as a railroad engineer. Beginning with simple survey jobs, he rose to chief engineer for the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad by 1853. By 1858, the thirty-one year old Mahone was not only the chief engineer but also the president of the railroad. Secession (which Mahone welcomed) and impending civil war called Mahone away from his railroad duties. By April of 1861, Billy Mahone found himself an officer in the Virginia infantry.

Mahone’s early war record as a brigade commander is solid but hardly spectacular. Mahone’s men helped construct and defend Drewry’s Bluff near Richmond and got their first real taste of action during the Peninsula Campaign. They fought hard at Second Manassas, and there General Mahone was wounded in the chest. When his wife was notified of his flesh wound, she commented that it must be serious, since little William had no flesh. Mahone recuperated in time to take part in the Battle of Fredericksburg in the winter of 1862, where he helped construct the defensive lines along General Longstreet’s front. The brigade fought at Chancellorsville and Salem Church, saw light action at Gettysburg, and squared off with the Federals at bloody Bristoe Station and Mine Run in late 1863.

To this point, Mahone had served commendably, even so far as to having been recommended for promotion. But “Bantam” Billy Mahone had yet to show his true capabilities. They became apparent in the thickets of the Wilderness.

Mahone’s brigade took part in the successful flank attack against the Army of the Potomac's left flank on May 6. General Longstreet’s wounding that day (eerily similar to Jackson’s wounding in the same vicinity almost exactly a year prior) led to Mahone taking command of a full division, which he led throughout the ensuing Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse and the back and forth clashes southward towards Petersburg.

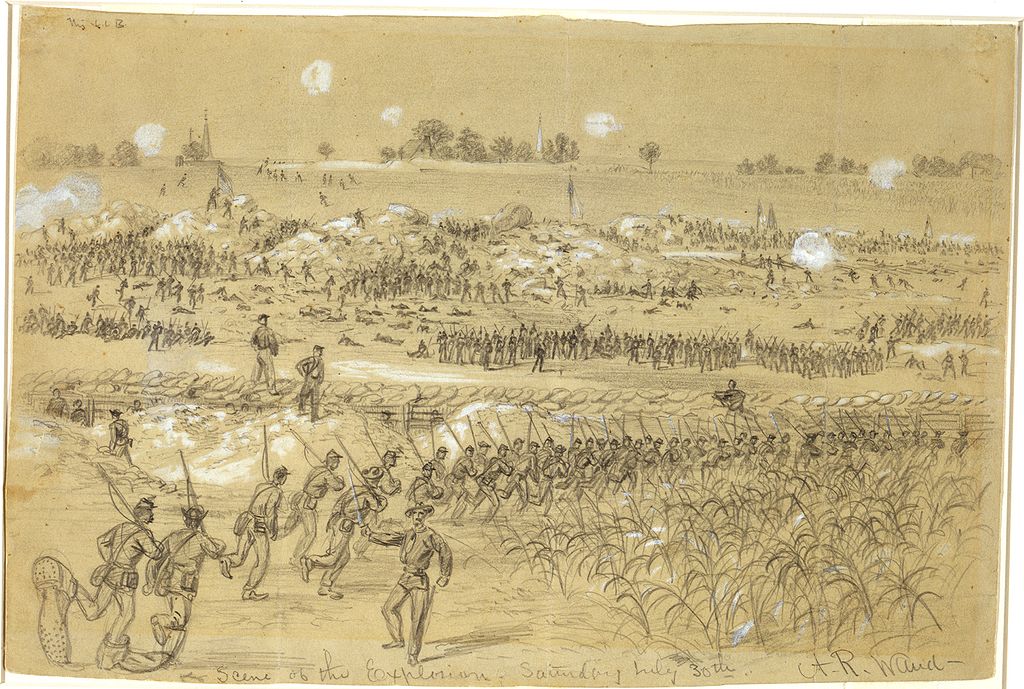

Just before 5 o’clock in the morning on July 30, 1864, approximately 8,000 pounds of gunpowder erupted in the midst of the Confederate trenches surrounding Petersburg, Virginia. Several hundred men were killed instantly. Federal soldiers charged into their terrible creation, a gaping crater that had blown a 135-ft. wide hole in the enemy line. Taking charge of the desperate situation, Mahone direct a stout defense that ensured that the Federals would never get beyond the Crater. Charles Venable, aide to General Lee, recalled after the war that “every message sent that day by General Lee (who was nearby), was sent to Gen. Mahone, as commander of the troops engaged repelling the enemy at the Crater and the adjacent line.” For his efforts, he was rewarded with the rank of major-general and the well-earned sobriquet “Hero of the Crater.” Mahone would command his division through the final months of the war all the way until Appomattox.

The end of the war brought Mahone back to the railroad business. From 1865 through 1876 Mahone presided over and help run the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad—a conglomeration of smaller lines that Mahone helped forge together in 1870. These business mergers gave Mahone his first taste of politics as he attempted to muster support for his business plans. He worked his way around the Conservatives (moderate Republicans and Democrats) and younger business leaders to gain the backing he needed to from the AM&O Railroad. All of his work came to naught, however, for economic crises in the early 1870’s forced Mahone out of business by 1876. Deciding to start a new track, Billy Mahone entered politics.

William Mahone offered himself up as a gubernatorial candidate for the Conservatives in 1877. The great issue of the day for Virginia was debt (an issue that resonates with us today). Mahone led a faction of the Conservative Party who wanted to “readjust” the debt levels. Much of Virginia’s debt came from the antebellum years, when West Virginia was still part of the Old Dominion. Mahone and his “Readjusters” wanted to see that portion of debt that belonged to new West Virginia struck down. By reducing the debt Virginia owed, funds would be freed up to pursue other public projects—notably schools. Mahone’s Readjuster faction lost the gubernatorial nomination to those who wanted to pay all the debt in full—“Funders.” Dismayed by their loss, Mahone and his followers split from the Conservatives in 1879 to form their own Readjuster Party.

From 1879 to 1883, Billy Mahone’s radical Readjuster Party would dominate Virginia politics. It was a party forged from a surprising and eclectic coalition of blacks, white Republicans, and moderate Democrats. This broad coalition translated into political power. Six of the ten Virginia Congressional districts lay in Readjuster hands. Two Readjusters were sent to the United States Senate…including, of course, Billy Mahone, who served until 1887. In 1882, both the Virginia General Assembly and the gubernatorial seat lay in Readjuster hands. Truly, the Readjusters possessed a unique opportunity to reshape the political landscape of Virginia and perhaps the South.

And try they did. The Readjusters advocated increased political suffrage for African-Americans—which would, of course, only add more voters to the Party. They worked strenuously to abolish proto-Jim Crow legislation and appoint blacks to state positions. Within the state legislature, three senators and eleven representatives were black. At a time when most ex-Confederates and conservative Democrats were scrambling to maintain their status as the political and racial elite, Billy Mahone and the Readjusters were upending the social order and empowering those who had been enslaved just years before.

The Readjusters, however, proved themselves to be not just racially but also socially progressive. With the state debt finally readjusted downward, funds were freed up to open more schools, hire more teachers, create new hospitals and mental institutions, charter new labor unions and cut property taxes. Poll taxes were abolished, the whipping-post outlawed, and attempts were made to increase government oversight and regulation on such goods as tobacco and fertilizer. William Mahone and the Readjusters were attempting to sculpt a radically new Virginia, one that could well serve as a model for a New South.

Such change drew criticism. Mahone was viewed by many as a selfish traitor, betraying the Southern cause and way of life for his own personal gain. As one political opponent decried, Billy cared “not a fig for either a Republican or a Democrat farther than he can use him for his own benefit. If a man be Mahoneite, he need no other recommendation or qualification.” It was certainly true that Mahone and others ran the Party as a strict, well-oiled political machine. Reporters noted that, “Southern Senators speak as bitterly of General Mahone and his followers as they did of carpet-baggers, scalawags, and niggers.” Mahone forged a successful political alliance, yes, but lost the faith and respect of many Southerners in doing so.

Billy Mahone’s Reconstruction Readjuster experiment came crashing down in 1883. In that year, Danville, Virginia was rocked by a race riot. Utilizing the riot to their gain, Conservative Democrats blamed Mahone and Readjuster policies as the wellsprings from which such racial disorder and violence was sprouting. The Readjuster Party suffered and soon succumbed to the political attacks. When Democrats took control of the General Assembly, they tore down the Readjuster political machine but, interestingly enough, kept many Readjuster reforms…thus preventing the party from popping back up.

Although the Readjusters were gone, Mahone stayed active in politics as a Republican—joining the weathered ranks of other famed Confederates who strayed to the party of Lincoln following the war, men like John Mosby and James Longstreet. Never again, however, did Billy Mahone enjoy the political power and success felt during the Readjuster movement.

The failure of Mahone’s Readjuster Party in Virginia in many ways represents a larger lost opportunity in the postwar American South. With the fall of the Confederacy, Reconstruction offered a brief time when genuine improvements in race relations could be made. Jim Crow legislation, segregation…these things had yet to be firmly entrenched. In short, the war had wiped the slate clean, and there existed a rare opportunity to bring about biracial cooperation and political involvement in the South. Virginia’s Readjuster movement, headed by ex-Confederate general Billy Mahone, represented such an opportunity.

Unfortunately, the Readjuster movement also represented the peak of such hopes in the South. The Readjuster movement failed, ultimately to be replaced with a Democratic regime that represented white supremacy and disenfranchisement of African-Americans in the South. Biracial political parties such as the Readjusters could enjoy political success in the 1880′s that would be unimaginable in the 1950′s. Billy Mahone’s reconstruction helped fuel a movement that envisioned a racially harmonious New South. Its failure (and the failure of such visionaries and movements across the South) ensured that African-American civil rights and political enfranchisement would not come about for nearly another century.

Further Reading and Sources:

Blumberg, Arnold. “Frail William Mahone Saved his Best Fighting for the Last Years of the War.” America’s Civil War. July, 2005.

Dufour, Charles L. Nine Men in Gray. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1963.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877. New York, NY: Perennial Classics, 1988.

Kollatz, Jr., Harry. “The Readjuster Party: William Mahone’s Bid to Alter History.” Richmond Magazine. April, 2007.

Levin, Kevin M. “William Mahone, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History.” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol 113, 4. Pgs. 378-412. 2005.

—. “William Mahone and the Readjusters to the Rescue.” Civil War Memory. February 5, 2012.

Luebke, Peter C. “William Mahone (1826-1895).” Encyclopedia Virginia. Brendan Wolfe, ed. March, 2011.

Pearson, C. C. “The Readjuster Movement in Virginia.” The American Historical Review, Vol. 21, 4. Pgs. 734-749. July, 1916.