Roundtable: The Civil War's Most Influential Event

/This post marks the first of Civil Discourse's Roundtable series, wherein we will periodically throw a common question to our authors (and the occasional guest!) in hopes of provoking thoughtful and diverse responses to some of the Civil War's (and it legacy's) most important issues. We encourage you to share your thoughts on our question below, and we may even include some of your most compelling answers in our post!

We're inaugurating this series with a very straightforward, yet undeniably juicy, question:

What event most influenced the outcome of the Civil War?

Becky Oakes:

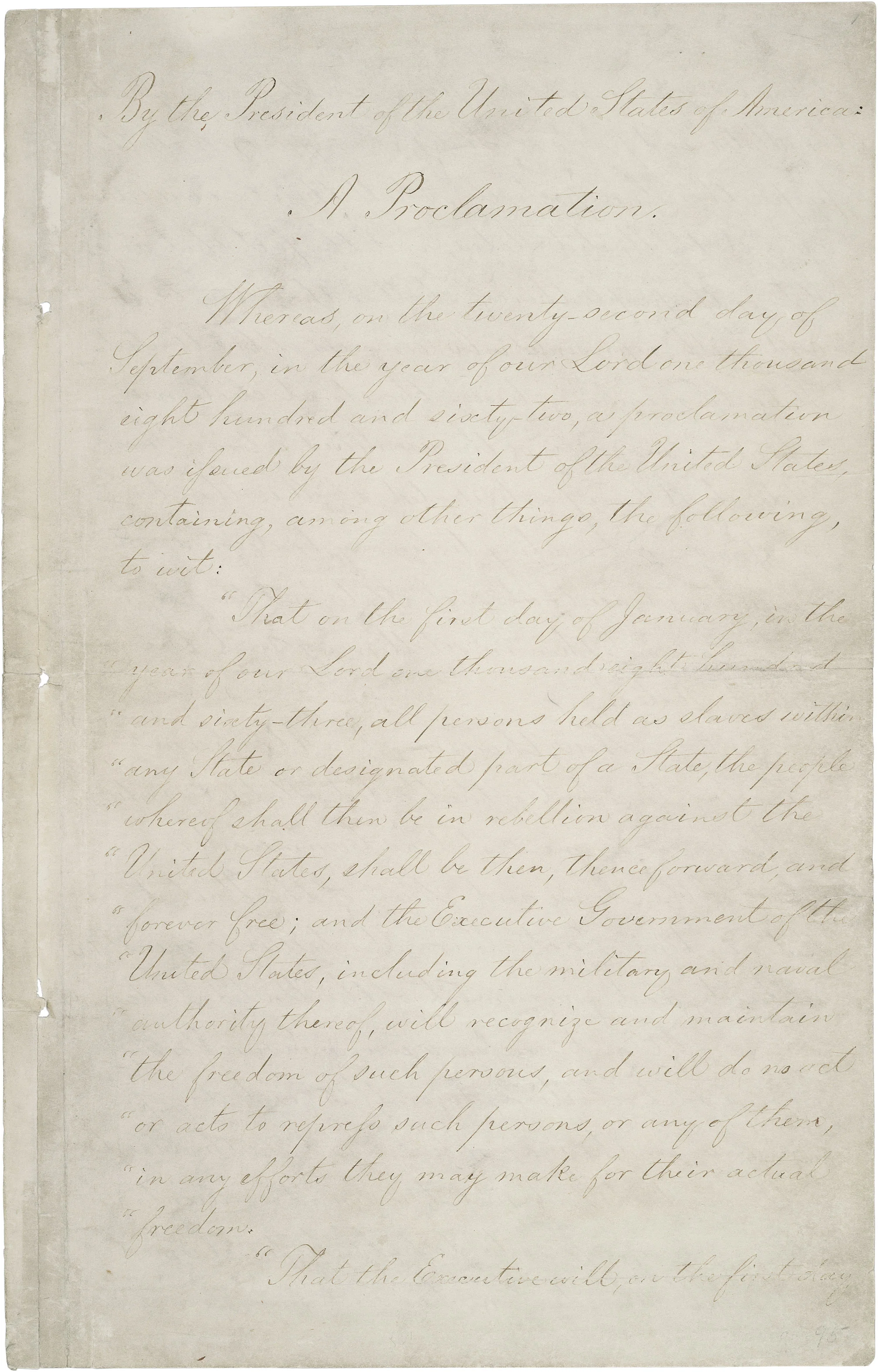

“That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free…”

Big words. Big ideas. A document that changed the world.

Pinpointing a singular event which had the most impact on the Civil War is not easy. These four years of conflict transformed our nation perhaps more than any other era in American history, and the consequences of these events are still being played out in the media, at our national battlefields, and even in our homes.

When presented with this question, a number of events immediately came to mind, including Ulysses S. Grant being given control of all Union armies, the fall of Vicksburg, and Sherman’s March to the Sea. But one instance I returned to time and again was the Emancipation Proclamation.

The ramifications of this one document were huge, and illustrate more than any other example how the course of war can be changed both on and off the battlefield. When analyzing historical events, the military, political, cultural, and social facets cannot be separated. Emancipation fundamentally changed how all of these aspects of society functioned.

From the beginning of the war to the end, the primary national purpose of the Confederacy’s war effort was the preservation of the institution of slavery. This was evident, prevalent, and widely understood. However, the Union’s purpose in fighting changed as the war developed. Initially, the primary concern of the United States’ government was to preserve the Union. This changed on January 1, 1863, with the official signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. The Civil War was now not only a war for reunification, but also a struggle for freedom.

Regardless of their personal views, all Union soldiers were now fighting to free enslaved people in the states in rebellion. This pronouncement was not met without dissent, and many soldiers and officers alike agonized over this new national purpose. Some of the divisions and opposition within the Union armies would last for the rest of the war.

For enslaved people in the Confederacy and freedmen in the North, this proclamation naturally had even greater repercussions. Although slaves had been practicing self-emancipation since before the war, and in increasing numbers with Union armies in close proximity, the Emancipation Proclamation gave former slaves in the Confederacy legal backing for seizing their freedom. Following the proclamation, freedmen were included in the Union army as United States Colored Troops (USCT), allowing African Americans to fight for the freedom of all, some even taking up arms against their former masters.

Although it fell under the umbrella of Lincoln’s executive war powers, the Emancipation Proclamation laid the groundwork for some of the most pivotal legislation to ever pass the United States Congress. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments made slavery illegal, redefined citizenship, and drastically expanded enfranchisement respectively.

Although we are still actively dealing with the effects of slavery and institutionalized racism over 150 years after the Civil War, the long and winding road to freedom was not only cut by the sword, but drawn by the pen.

Zac Cowsert:

Upon receipt of the Union disaster as Second Manassas in August, 1862, British Prime Minister penned a note to his Foreign Secretary John Russell. “The Federals got a very complete smashing,” Palmerston wrote, “and it seems not altogether unlikely that still greater disasters await them…would it not be time for us to consider whether…England and France might not address the contending parties and recommend an arrangement upon the basis of separation?” Secretary Russell agreed, and they both decided to hinge any further actions—any possibility of British mediation of the Civil War—on the outcome of a battle shaping up in Maryland in the last weeks of the summer. “If the Federals sustain a great defeat, they may be at once ready for mediation,” Palmerston mused. “If, one the other hand, they should have the best of it, we may wait awhile and see what may follow.”

While Palmerston and Russell waited for news across the pond, Abraham Lincoln, ensconced in muggy Washington D.C., also awaited news from Maryland. The American president sat on a draft of a proclamation that would set all slaves in areas of rebellion free—a document that would radically alter the course of the war and place the abolition of slavery at its heart. But Lincoln needed a victory to support such a radical policy, and he anxiously waited for word from the front.

Meanwhile, Confederate General Robert E. Lee led his troops north, heading the first serious Confederate invasion of the North; simultaneously, Confederate troops occupied Kentucky...twin Southern invasions designed to bring the North to heel. In the minds of General Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Southern independence may well depend on how these twin invasions fared.

The much-anticipated battle—upon which the fate of peoples and nations alike hinged—finally played out along the banks of Antietam Creek on September 17, 1862. The deadly contest resulted in the bloodiest day in American history and a tenuous Union victory, and with it the war changed forever. With a Union victory in the East finally in hand, Abraham Lincoln declared to his cabinet that "I think the time has come," and he issued his Emancipation Proclamation. The Proclamation undercut the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy—slavery—and set the stage for the enlistment of black soldiers into the Union army (at a time when Confederate recruits were becoming harder to come by). Although the Proclamation initially endured a scathing reception in Europe, it eventually transformed the conflict in European eyes into a war over slavery, ending any likelihood of European mediation or intervention. Moreover, the defeat of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia ended a summer of great opportunity for the Confederacy.

Although many similar moments of importance transpired throughout the war years, I would argue that the summer of 1862—and especially the lynchpin Union victory at Antietam—left the greatest impact on the war’s course, setting in motion events that empowered the liberation of an enslaved race and ensured the young Confederacy would fight the war unaided.

Chuck Welsko:

I am going to offer what I hope is a different answer to today's question. When we talk about the event that most influenced the outcome of the Civil War, I think there are a couple of answers that always pop up: Antietam, Gettysburg, or Vicksburg. I would argue that the fall of Atlanta in early September, 1864, rather than those more famous battles, had deeper impact on the outcome of the Civil War. My rationale stems from the fact that the political, as well as the psychological, ramifications of Atlanta’s capture guaranteed Lincoln’s reelection.

Returning Lincoln to the White House was an essential goal for many pro-war Northerners in 1864, as it became clear the war would not end before the November presidential election. However, there was no guarantee that Lincoln would win or even appear at the head of the Republican ticket. As shocking as it may sound today, in a time when Lincoln is one of the idolized presidents, some Republicans advocated running John C. Fremont or a more radical candidate instead of incumbent Lincoln. Additionally, throughout the summer of 1864, Lincoln himself remained uncertain of his ability to secure reelection.

A large part of Lincoln's woes were due to the lack of recent military successes. Admittedly, the Overland Campaign from the Wilderness down to Petersburg brought the Union Army extremely close to severing the supply lines to Richmond. Yet, while Grant’s persistence put the Union on the cusp of taking the Confederate capital, it had come at tremendous cost. Tens of thousands of Union soldiers perished in the relentless assault on the Army of Northern Virginia. At home, Northerners grew weary of war, as it rightly appeared that the four summer of conflict would pass with the possibility of a fifth to follow. The prospects for the Union war effort and Lincoln’s reelection appeared dim as Grant seemingly pounded his head against Petersburg's defenses.

Approaching the presidential election of 1864, the North had a dangerous mix of war weariness, rising agitation by Copperheads, and a lack of military successes. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta arrived at the perfect time, offering important military considerations and an impressive political windfall for Lincoln (and really all Republicans). Militarily, the fall of Atlanta further segmented the Confederacy, depriving them of an important logistical hub. Politically, it offered Lincoln the success he needed to convince the North that his course would ultimately succeed. Therefore, although some contemporaries alleged that Sherman used fire haphazardly in Atlanta, his seizure of that city reignited the flames of confidence in the Lincoln administration, carrying the Union onward to the end of the war.

Katie Thompson:

When asked this question in a military sense I usually answer that there are three battlefield turning points that led to Union victory. Many people consider Gettysburg the turning point of the Civil War, but that is largely due to the memory constructed after the battle and in the post-war period. Gettysburg is important, however, as a morale turning point since it was a major victory against Robert E. Lee that turned him away from the North and ultimately led to a long string of stalemates or defeats for the Army of Northern Virginia. In terms of military strategy, Vicksburg is much more important than Gettysburg because it cut the Confederacy in half and made communication and travel between the western states and the center of government in the east much more difficult. Antietam is important as well, the battle's outcome prompting President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and discouraging European involvement in the conflict.

Looking on a broad scale, I would argue that the event which shaped the outcome of the Civil War the most in terms of victory and the long-term outcome of the war is President Lincoln’s decision to pursue emancipation as a goal during the war. True, the Emancipation Proclamation did not have much strength behind it when it was first issued, but it prevented European involvement from countries who did not want to get into a fight over slavery. It led to a Union victory that not only reunited the country, but also ended the institution of slavery. Lincoln knew that striking at slavery would target the very foundation of the Confederacy and weaken its ability to fight the war. With emancipation, the Civil War became more than just a civil conflict, but a larger war of freedom. Even more than the immediate impact emancipation had on the war’s outcome, the lasting legacy of Lincoln’s actions echo today in the very conflicts we still have over Civil War memory. The Emancipation Proclamation, though weak in itself, led to the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments granting new freedoms and rights to African-Americans and the period of Reconstruction rapidly turned the social structure of the South (and the entire United States) on its head. While Reconstruction pushed rights for new African-American citizens forward, the sudden end of Reconstruction and the backlash from southern citizens led to a long period of discrimination, violence, and disenfranchisement that continued well into the twentieth-century (and some would argue has not entirely ended today). The difficulties of reconstructing a nation and changing a social hierarchy that had been based on race almost since the beginning of its history proved difficult due to the sudden changes emancipation brought to the United States, and that contested meaning and memory has proved to be much of the Civil War’s legacy

Becca Capobianco:

After considering a variety of events such as the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln's decision to appoint Grant as Commander-in-Chief of all Union armies, and the 13th Amendment, I will have to play devil's advocate and argue that no single event influenced the outcome of the war the most. Working at or visiting a Civil War battlefield you tend to get bogged down in the details--who commanded the 3rd division? How many cannons were on that hill? If that cannon had exploded just a little more vehemently, which generals would not have survived? There are intricacies to battles that resonate through events with such force they are hard to measure.

The same is true with seemingly further-reaching decisions, the ones that have massive impact from the moment they are made. Something I have always tried to stress when giving a tour of the battlefield is how those smaller microcosms of the war, those smaller decision--like just when to move that artillery battery behind the lines--illustrate that ware are fought in inches. They are lived. Just like decisions in our own lives, each event has impact in a continuum, circles on the water getter bigger as they pick up momentum.

Roundtable Review:

As our answers above illustrate, a number of momentous documents, events, and people shaped the war. Asked the same question, our authors largely emerged with different answers: Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, the Battle of Antietam, the fall of Atlanta, the possibility that no single moment primarily shaped the war. Still, despite the seemingly disparate answers, common themes emerged. Clearly emancipation and the abolition of slavery lay at the root of many of our answers. Also important was the Emancipation Proclamation's creator Abraham Lincoln, who shows up in many of our answers. Intriguingly, several of our author's answers pointed to the significance of emancipation dooming the prospect of European intervention...perhaps suggesting that the Confederacy's only hope of victory lie overseas? Equally revealing is the absence of several oft-cited turning points; Gettyburg, Vicksburg are absent, no mention is made of the blockade either.

Having read our choices, what are yours? Feel free to post your thoughts below! Compelling answers may find their way into this post!

Roundtable Contributors:

Becca Capobianco received her master's degree in American and public history from Villanova University. Becca worked as an educational consultant at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park; she now works at Great Smoky Mountains National Park. She has worked at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, PA, and as an adjunct faculty member at Germanna Community College.

Zac Cowsert is currently pursuing his doctorate in American history at West Virginia University, where he also earned his master's degree. His research focuses on the Civil War experience of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory. Zac attended college at Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport, and he has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, recently completed her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. history and public history at West Virginia University. She will begin her doctoral work at WVU in the fall. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments. She also studies National Park Service history, and has worked at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, Gettysburg National Military Park, and the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College.

Katie Logothetis Thompson earned a BA in History from Siena College in her homestate of New York. She received her MA in History from West Virginia University, and she is now a doctoral candidate at WVU. Her research explores how Civil War soldiers attempted to cope with their wartime experiences. Katie has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park in Virginia in addition to other academic and public history projects.

Chuck Welsko is currently a doctoral student in 19th-century American history at West Virginia University, where he also received his master’s degree. An alum of Moravian College in Pennsylvania, he has also worked for local museums and interned with the National Park Service. Chuck’s research focuses on the mid-Atlantic region, in particular the intersection between politics, rhetoric, and the conceptualizations of loyalty during the Civil War Era.