Sanitary Measure or Unchecked Despotism? The Fourteenth Amendment, the Slaughter-House Cases, and Radical Reconstruction

/How does the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution relate to a group of disgruntled butchers? In 1873, the United States Supreme Court struggled to answer exactly this question.

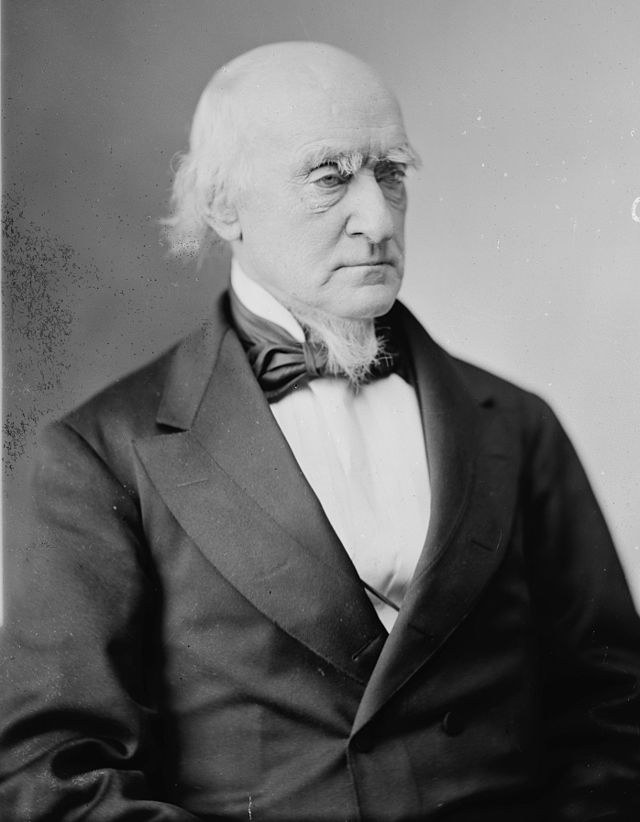

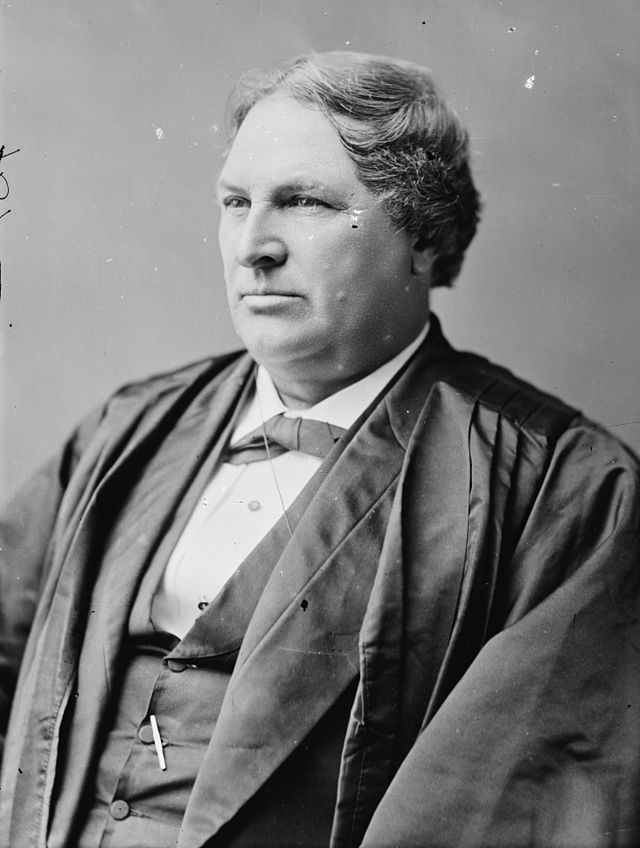

Perhaps no image better captured the tumultuous and confused nature of the Reconstruction Era than former Supreme Court Justice John Campbell during the 1873 Slaughter-House Cases. A former slave owner who served as the Assistant Secretary of War for the Confederacy, Campbell oddly found himself arguing against states rights in an attempt to overturn a Louisiana state statute. When the Reconstructionist, Republican-dominated legislature of Louisiana incorporated all the slaughterhouses within New Orleans, giving a single company the exclusive right to slaughter within the city, no one expected the butcher’s protests to lead to the first interpretation of the new Fourteenth Amendment by the nation’s highest court. Campbell, however, quickly saw an opportunity. By claiming that the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was “to establish through the whole jurisdiction of the United States one people, and that every member of the empire shall understand and appreciate the constitutional fact that his privileges and immunities cannot be abridged by state authority,” Campbell was attempting to do more than win a court case for the butchers of New Orleans. He was hoping to turn Reconstruction Era legislation against itself.

The Slaughter-House Cases (1873) were rife with often-cited irony. Most obviously was the fact that the first Supreme Court interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment did not involve a case concerning former slaves, but instead dealt with white butchers from New Orleans squabbling with other white butchers over a statute enacted as a sanitation measure by a Reconstructionist legislature. This led to one of the most controversial opinions ever handed down. In a five to four decision, a highly split court just barely voted to uphold the state’s statute and allow the slaughterhouse monopoly to exist. The author of the majority opinion, Justice Samuel Miller, has been heavily criticized for giving a narrow interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment as applying specifically to former slaves. In addition to this, Miller also stated “there is a citizenship of the United States, and a citizenship of the State, which are distinct from each other,” which took a step back in the process of defining citizenship on a national level and effectively denied extending the Bill of Rights to the state. However, much of this criticism is retrospective. To truly understand the motives behind Miller’s opinion, one must consider the practical concerns such as sanitation in New Orleans, racial tensions, and a Republican Party that was beginning to schism, as well as the legislative intent of the framers of the new amendments. When viewed in this context, Miller’s opinion can be interpreted as a reactionary measure not intended to be the final decree on the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.

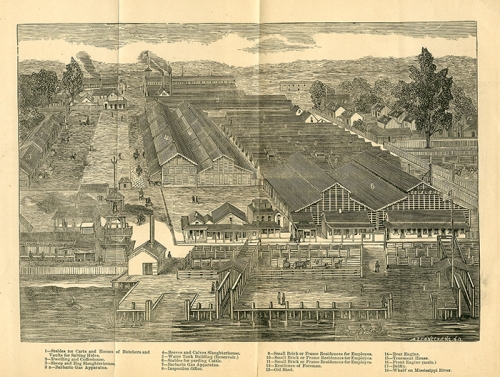

The foundations of the Slaughter-House Cases extend far before the American Civil War, with the founding of a town named New Orleans in 1718. The Crescent City, nicknamed such for its location on a bend in the Mississippi River, expanded into a world-class trading center with a rapidly growing population in the first half of the nineteenth century. However, the city’s subtropical temperatures, humid climate, and low elevation caused drainage and sanitation issues from the beginning. The issues of topography were so extreme that one observer in 1853 was noted as saying that New Orleans was founded on a site “which only the madness of commercial lust could have tempted men to occupy.” The city became infamous for its squalor, and the worst offenders were the slaughterhouses.

Unregulated and numerous, slaughterhouses were scattered throughout antebellum New Orleans, with a particular concentration in an area a few miles upstream of the city, known as Slaughterhouse Point. The slaughterhouses operated alongside other businesses, homes, and even hospitals, herding over 300,000 animals every year through the city streets before bloodily disposing of them. An even larger problem was the waste produced by the slaughterhouses, which would usually be thrown haphazardly into the streets or directly into the Mississippi River. “Barrels filled with entrails, blood, urine, dung and other refuse, portions in an advanced stage of decomposition are constantly being thrown into the river,” one New Orleans doctor described this horrid scene with candor, and continued to say that the waste was “poisoning the air with offensive smells and necessarily contaminating the water near the bank for miles.”

One result of the deplorable sanitary conditions was the frequent outbreak of epidemics, particularly cholera and yellow fever. One particular attack of yellow fever in 1853 killed one-tenth of the population, and drove the city to a standstill while they cared for the sick and disposed of the dead. This was followed by three epidemics nearly as severe in 1854, 1855, and 1858. It was under these conditions that New Orleans was occupied by federal troops under Benjamin Butler during the Civil War.

Upon taking control of the surrendered city in May of 1862, Butler was appalled by the sanitary conditions. Describing the city’s streets as “reeking with putrefying filth,” the Union commander was soon informed, “the enormous stink…was no more than usual.” Butler immediately launched a massive cleanup effort in the city, combining quarantine and sanitation regulations. Although the Confederate sympathizers of New Orleans highly resented the presence of Butler and his troops, the sanitation efforts he put in place were a great success in preventing disease. At the end of the Civil War, sanitary conditions in New Orleans were the best they had ever been. However, the departure of federal troops, as well as changes in the cattle market brought on by sectional conflict, would soon make legislative regulations necessary.

The American Civil War had left the nation with a cattle shortage except in one location: Texas. Throughout the war, Texas cattle farmers had been cut off from all available markets. Therefore, while the rest of the nation was suffering from a shortage in the supply of beef, the cattle herds in Texas had been growing exponentially. In 1865, it was said that in Texas there were “probably 5,000,000 cattle – and no market.” When the newly reunified United States turned to Texas for its beef supply, businessmen in New Orleans hoped that the plentiful, low priced cattle would have to pass through the Crescent City in order to reach the eager, high-priced markets of the rest of the nation. This hope for an economic boon, coupled with deteriorating sanitation conditions, led directly to the state legislature enacting the Slaughterhouse Act of March 8, 1869.

This act facilitated several major changes in how slaughtering in New Orleans was carried out. Most significantly, this legislation made it illegal to “land, keep or slaughter any cattle…or other animals, or to have, keep or establish any stock landing, yards, pens, slaughter houses or abattoirs” within the city of New Orleans. The only exception to this rule was the “Crescent City Stock Landing and Slaughterhouse Company,” a corporation established by the state legislature and granted the exclusive privilege of slaughtering within the city. In order to maintain this charter, the Crescent City Company was required to “build and complete a grand slaughter house of sufficient capacity to accommodate all butchers, and in which to slaughter five hundred animals per day.” Provided all requirements were met by June 1, 1869, and maintained, the company’s charter was to last twenty-five years. Unsurprisingly, the most controversial aspect of this act was the establishment of a monopoly by the state.

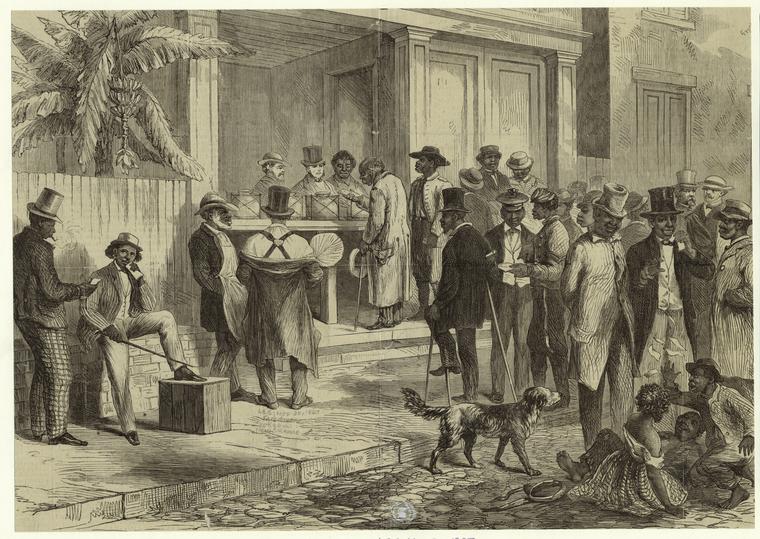

The underlying current of racial and political tensions in Louisiana at this time led to heightened friction. Louisiana was one of only three states to have a black majority. In addition to this, New Orleans in particular had an unusually large free, wealthy, and educated black community before the Civil War. These issues factored in to the establishment of the Republican Party in Louisiana, which included three distinct groups: Free State whites, African Americans (both ex-slaves and those who were never enslaved), and transplanted Northerners. One particular Union army officer and lawyer, twenty-six year old Henry Clay Warmoth, would become Louisiana’s youngest governor in 1868, and it would be under his tenure that the Slaughterhouse Act was established. Although the elections of 1868 came with a decisive Republican majority in the state legislature, in addition to a new state constitution, a schism was already forming in the Republican party. Warmoth and other white Republicans distinguished themselves from black “radical” Republicans, and this conflict would lead to the deterioration of the party in Louisiana politics.

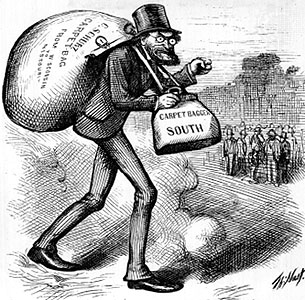

Protests began almost immediately after the creation of the Slaughterhouse Act, and these protests were inseparable from the other political tensions of the time. Rampant rumors of corruption and bribery circulated through New Orleans, particularly through organs such as the Daily Picayune or the Ouachita Telegraph, two newspapers bitterly opposed to both the Slaughterhouse Act and the Republican government. For example, on March 7 1869, the Daily Picayune described the representatives in the legislature as “greedy for the rapid acquisition of wealth and utterly unscrupulous as to the means of getting it.” Overall, a contributing factor to the dissent amongst the populace was that many members of the old ruling class did not recognize the new Republican government as legitimate. Instead, they described the black representatives and carpetbaggers in terms such as “ignorant negroes cooperating with a gang of white adventurers.” No statutes enacted by this congress were readily accepted, let alone one establishing a monopoly.

Not only did those opposing the bill suggest that the Act was achieved through bribery, but they more importantly maintained that the monopoly was a violation of the “privileges and immunities” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which stated, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States.” The existence of the Butchers Benevolent Association of New Orleans, created in 1866, allowed the butchers themselves to speedily and decisively respond to the Slaughterhouse Act. They managed to organize protest meetings and write resolutions, such as one that stated they would not “submit patiently to a measure which invades their natural and constitutional rights.” Their legal representation came in the form of John Campbell. A Georgia native, Campbell had been appointed to the United States Supreme Court in 1853. However, when secession broke out, Campbell left the court.

The opposing arguments that would be carried all the way to the Supreme Court did not take long to form. Those in support of the Slaughterhouse Act saw its establishment as purely a sanitation measure and well within the police powers of the state. The legal council appointed for the Crescent City Company was Randell Hunt and Christian Roselius, two of the most distinguished members of the New Orleans bar. As the Crescent City Company began making plans to have their facility ready by the June 1st deadline, the opposition began filing numerous appeals against the company. Attempts by the company to quell the opposition failed, and a butcher’s boycott involved the rest of the city through the lack of fresh beef. Eventually, six cases would be heard in the district courts, and then taken to the Louisiana State Supreme Court.

Campbell, arguing for the butchers, made three distinct points. First, he claimed that bribery had been involved in the establishment of the Crescent City Company. Second, he argued that the statue was in violation of the state constitution because it had been signed by Governor Warmoth after the legislature had adjourned, and not within a five-day period. Finally, the former advocate of states’ rights stated that the statute was a blatant violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Attorney General Belden, arguing for the company, expressed his opinion that the amendment to the Constitution had “not the remotest application to the solution of the question, presented by the record.” Furthermore, he argued that the Slaughterhouse Act was based on police powers, and that nothing in the act prohibits any individual from being a butcher. In a three to one decision, the Louisiana Supreme Court upheld the Slaughterhouse Act.

The next few years would be a time of great confusion for the butchers in New Orleans. Realizing that the inclusion of the Fourteenth Amendment in their argument may enable them to appeal to the federal courts, the butchers’ attorneys visited Supreme Court Justice Joseph P. Bradley as he was attending to circuit duties in Galveston, Texas. The butchers were hoping that Bradley would issue a writ of error, which would hold the Louisiana Supreme Court’s decision in abeyance until the United States Supreme Court heard the case. Bradley issued the injunction, and went on to give a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment, stating that it “must be examined with more attention and care.” This action not only reopened the case, but also set it on the path to being heard by the nation’s highest court.

The court that heard the Slaugher-House Cases was heavily Republican. Despite the fact that the vast majority of the court belonged to the same political party, the votes for the Slaughter-House Cases were nearly split at five to four. This may be a reflection of the difficult position the justices faced during the era of Reconstruction. In general, the justices tended to be more conservative than the Radical Republicans in Congress, and they began to differ amongst themselves as they dealt with a seemingly endless stream of landmark cases and controversial issues.

The Supreme Court heard the final arguments in the Slaugher-House Cases between February 3rd and 5th of 1873. Once again arguing on behalf of the butchers, John Campbell went a radically large step further than his previous arguments in the briefs he prepared for the Supreme Court. He cited not only the Fourteenth Amendment’s “privileges and immunities” clause, but also the Thirteenth Amendment’s reference to “slavery and involuntary servitude” to argue that his clients were forced into a form of involuntary servitude by the Slaughterhouse Act. He went on to state, “We have never supposed that these Constitutional Enactments had any particular or limited reference to Negro slavery. The words employed do not describe that form of slavery and that only. They are absolute, universal.” Although Campbell conceded that the plight faced by the butchers of New Orleans was not directly comparable to chattel slavery, he maintained, “the common rights of men have been taken away and have become the sole and exclusive privilege of a single corporation.” In his conclusion, Campbell delegitimized the claim that the Slaughterhouse Act was concerned with public health as well as the Reconstruction legislature of Louisiana itself, referring to its measures as “despotism.”

Arguing on behalf of the Crescent City Company, Thomas Durant focused on legitimizing the state’s right to utilize police powers, particularly for the general good. Durant placed the Slaughterhouse Act firmly into the realm of state police power, enacted for the health and general benefit of the population. He further states that “if the sovereign power judges that the interests of society will be better promoted by making such rights the exclusive privilege of a few, or of the state itself, this private right must yield to the public good.” Finally, Durant argued that the privileges and immunities clause applied only to persons of African descent, and a wider interpretation could lead to a “slippery slope” that would destroy the federalist system altogether.

On April 14, 1873, the eighth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, the Supreme Court handed down the first interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The case was anything but clear, something reflected in the final five to four decision. Just over half the court wished to focus on the context in which the Fourteenth Amendment was written, denying a wider interpretation and upholding the Slaughterhouse Act as an appropriate police power. Alternatively, just under half of the court favored a wider interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment to include all persons as opposed to exclusively former slaves, and thus found the Slaughterhouse Act to be in violation of the new constitutional legislation. By a narrow margin, the United States Supreme Court upheld the Louisiana statute, and thus legitimized the Crescent City Company’s monopoly.

Justice Samuel Miller, appointed by Lincoln, was chosen to write this controversial opinion. Although not the senior justice in the majority, he was the obvious choice due to his personal background. Not only had he served on a number of cases involving Constitutional issues, but he also had varied experiences in the realm of public health. Miller was a former physician, and had written specifically on the dangers of cholera epidemics caused by polluted water. He also lived in Keokuk, Iowa, which was once an extremely busy pork-packing center, for about a decade. Therefore, he most likely understood and sympathized with the necessity for sanitation reforms in cities with large slaughterhouses. Since he had no formal legal training, his interpretations were oftentimes based on logic rather than legal doctrine. Miller was a moderate and a pragmatist, and his opinion reflected this.

Miller clarified that this statute does not “prevent the butcher from doing his own slaughtering,” and therefore Miller rejected the argument that the butchers were deprived of their right to labor or forced into any type of involuntary servitude. The power “exercised by the legislature of Louisiana” was then defined as a police power, which has “always conceded to belong to the States.” Under this interpretation, the Slaughterhouse Act was created as a sanitation measure.

If Miller had ended his opinion there, it would not have been nearly as controversial. It was not required of Miller to interpret the newly added amendments to the Constitution; in fact, Slaughter-House Cases almost certainly was not the ideal case with which to do this. However, he went on to describe a narrow interpretation of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendment based on what he believed to be legislative intent. Miller aptly suggests that “lying at the foundation of each [amendment], and without which none of them would have been even suggested,” is the “freedom of the slave race, the security and firm establishment of that freedom, and the protection of the newly-made freeman and citizen from the oppressions of those who had formerly exercised unlimited dominion over him.” Miller explicitly stated that all three of the new amendments were intended to address issues of race. However, an often-ignored caveat to this statement was Miller’s declaration “We do not say that no one else but the negro can share in this protection.” This could have implied that Miller did not intend his opinion in the Slaughter-House Cases to be the Supreme Court’s final word on the subject of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, but instead specific to this particular case.

The most widely criticized portion of Miller’s opinion by far was his commentary on citizenship. By writing, “It is quite clear, then, that there is a citizenship of the United States, and a citizenship of a State, which are distinct from each other, and which depend upon different characteristics or circumstances in the individual,” he allowed for states to be able to limit or grant privileges and immunities outside of those guaranteed by United States citizenship. For example, Miller quickly ascertained that the rights being claimed by the butchers were not privileges and immunities exclusively granted to citizens of the United States, and therefore was a state matter. Unfortunately, this interpretation would later be adopted by the states in order to deprive newly freed men of their rights as citizens.

This was almost certainly not Miller’s intent. Post-reconstruction racial oppression could not be predicted in 1873; at the time of Miller’s opinion, Reconstructionist governments in the South were the biggest champions of racial equality. In this context, it made sense for Miller to abide by the interpretation that the new amendments did not necessarily signify a major change in the federal system.

In their comprehensive work on the Slaughter-House Cases, Ronald Labbé and Jonathan Lurie suggest that John Campbell’s ulterior objective for his extensive use of Reconstruction legislation in his argument was to “employ the new constitutional realities of Reconstruction as a legal weapon to bring about its ultimate demise.” He despised biracial government, as evidence by his complaints in a letter to his daughter, “We have the African in place all about us. They are jurors, post office clerks, custom house officers & day by day they barter away their obligations and duties.” He seemed to be an unyielding advocate of the Old South, and if the New Orleans slogan “Leave it to God and Mr. Campbell” was any indication, he would not rest until the progress made during Reconstruction was undone. If this were the case, it would be easier to understand the pragmatic Miller’s opinion as reactionary.

Overall, Samuel Miller’s narrow interpretation of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments as applying to the status of freed slaves and little else was not an attempt to limit individual freedom. Instead, it was a measure taken to prevent men such as Campbell from using the new constitutional legislation to destroy Reconstruction on a state level. The pragmatic Miller recognized the Slaughterhouse Act as a sanitation measure enacted by Louisiana’s police powers, but also saw the danger in letting an opportunity to support the then strong Republican state governments pass.

Miller’s opinion may have been shortsighted, sensible, or both. However, this case was eventually corrupted as a tool for racial oppression, illustrating the power our nation’s highest court wields, even unintentionally. Few in 1873 could have predicted that a handful of butchers trying to stave off a monopoly would help unleash an institutionalized system of racial violence and inequality in the form of the Jim Crow South.

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, is currently finishing her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. History and Public History at West Virginia University. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments. She also studies National Park Service history, and has worked at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, Gettysburg National Military Park, and the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College.

Sources and Further Reading:

Adams, Eva Doris. The Slaughterhouse Cases: The First Interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Ann Arbor, MI: A Bell & Howell Company, 1996.

Amendment XIV, Section 1, July 9, 1868.

Berger, Raoul. Government by Judiciary: The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977.

Billings, Carol. “The Slaughterhouse Cases.” De Novo: The Newsletter of The Law Library of Louisiana 5, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 4-5.

Current, Richard N. Those Terrible Carpetbaggers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Daily Picayune. Library of Congress Historical Newspapers. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov (accessed April 1, 2013)

Franklin, Mitchell. “The Foundations and Meaning of the Slaughterhouse Cases.” Tulane Law Review XVIII (October 1943): 1-88.

Kurland, Phillip B., and Gerhard Casper, eds. Landmark Briefs and Arguments of the Supreme Court of the United States: Constitutional Law. Vol. 6. Arlington, VA: University Publications of America, 1975.

Labbé, Ronald M. and Jonathan Lurie. The Slaughterhouse Cases: Regulation, Reconstruction, and the Fourteenth Amendment. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2003.

The Louisiana Democrat. Library of Congress Historical Newspapers. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov (accessed April 1, 2013)

Ouachita Telegraph. Library of Congress Historical Newspapers. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov (accessed April 1, 2013)

Ross, Michael A. Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court during the Civil War Era. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003.

Scott, John Anthony. “Justice Bradley’s Evolving Concept of the Fourteenth Amendment From the Slaughterhouse Cases to the Civil Rights Cases.” Rutgers Law Review 25, no. 4 (1970): 552-69.

Slaughter-house Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873).

Warmoth, Henry Clay. War, Politics and Reconstruction: Stormy Days in Louisiana. New York: Macmillan, 1930.