The Creation of Gettysburg National Cemetery

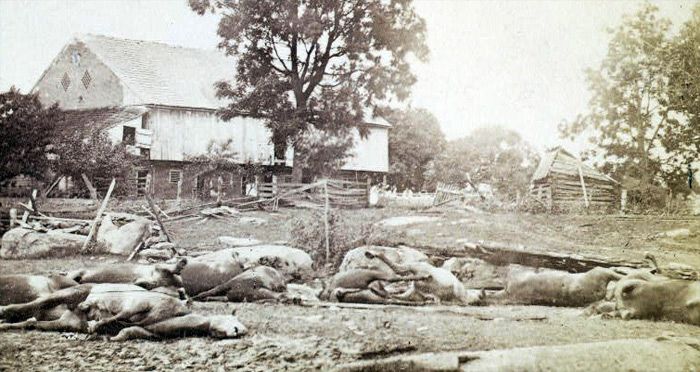

/On July 4th, 1863 Meade’s Union army rejoiced as the sights and sounds of a Confederate army in retreat ensured them of their victory. For the North, Independence Day 1863 was a day of rejoicing and confirmation with victory at both Gettysburg and Vicksburg. But in the midst of victory, July 4th was also sobering for the men who fought around that Pennsylvania town for it was the first chance they had to inspect the battlefield and attend to the dead. After three days of fighting, 7,058 dead men lay scattered in and around the town: 3,903 Confederates and 3,155 Federals. The nearest comparison in terms of outright dead bodies was the Battle of Antietam with 3,900. In addition to the human corpses, there were 3,000 dead horses, many injured horses that also would need to be destroyed, and large numbers of dead mules and civilian livestock.

The Union soldiers and Gettysburg civilians that looked over the battlefield on July 4th saw a level of death and destruction that was overwhelming and seemingly impossible to take care of.

Faced with over 7,000 human bodies to bury and many more wounded to care for, the Union army only paused for a day before it too left Gettysburg in pursuit of Lee’s retreating army, leaving doctors behind to care for the living and provost marshals to organize the civilian population into a burial corps. The 2,400 citizens of Gettysburg, traumatized by three days of war in and around their homes, would now have to cope with roughly 22,000 wounded and an estimated 6 million pounds of carcasses, both human and animal.

Provost Marshal Captain W.W. Smith published a notice to the citizens of Gettysburg:

To all Citizens,

Men, Horses and Wagons wanted immediately, to bury the dead and to cleanse our streets, in such a way to guard against a pestilence. Every good citizen can be of use by reporting himself, at once, to Capt. W. W. Smith, acting Provost

Marshal, Office, N. E. Corner, Centre Square.

Not surprisingly, Captain Smith found it difficult to recruit civilians to help with the clean up and burial efforts. Those who did volunteer, or were recruited, set out to complete the grisly task of burying human remains that had lain unattended for several days. These crews separated the Confederate soldiers from the Union, pulled the dead into lines or dug single graves where they fell, and buried them as best as they could. Many bodies were buried singly where they fell. Burial crews dragged bodies into line by tying rope or a belt around the legs or chest of the corpse or used a stretcher to carry them, and then used poles or rails to roll the remains into the grave to avoid physically handling them.

This process was done hastily and haphazardly, leaving marked and unmarked graves crisscrossing the battlefield. The goal of this early process was not to bury and identify the dead in an orderly fashion; instead, crews worked quickly to bury the human dead and burn animal carcasses to mitigate the stench of rotting flesh and prevent the spread of disease. There was no official map or roster to mark the location of the graves and many of the bodies buried in this process were not identified by name or regiment. In some cases individuals noted the location of a specific burial in a letter or a diary or a local resident kept records of burials on or near their property, but largely there was no record kept of the Gettysburg burials. This lack of records caused much heartbreak in the weeks after the battle as friends and relatives poured into Gettysburg looking for lost loved ones who they knew or feared had perished in the battle. The Adams Sentinel marked their forlorn presence on July 21, 1863: “Some have to go away cheerless and unsatisfied, the last resting-place of their friends not being identified, from the vast amount that were hurried into their mother-earth, without a mark to tell who lies there. This is painful to a father, a mother, a wife, a sister; but such is the inevitable consequence of a fearful and tremendous battle, like that of the three days of Gettysburg.”

Immediately after the initial burial process ended there were calls in the North for the development of a centralized cemetery to hold the Union dead. Families had been retrieving the bodies of loved ones since the battle, but most did not have the money for the embalming and transportation necessary to return bodies home for burial. The hasty burials on the field also raised new concerns about health issues, particularly from farmers whose crop fields were full of graves. Under an 1862 Pennsylvania law that required the state to care for its war wounded and the burial of the dead, Adams Country residents petitioned Governor Andrew Curtin for a cemetery to hold all the Pennsylvanians killed at Gettysburg. Gettysburg attorney David McConaughy wrote Curtin suggesting that all Pennsylvania soldiers be buried at the state’s expense at Evergreen Cemetery, of which he was President. In anticipation of a decision, McConaughy began to make agreements with neighboring landowners to buy land to expand the cemetery.

The idea to create a national cemetery was first proposed by ex-army surgeon Theodore Dimon who presented the idea for a cemetery for all the Union dead to Curtin’s appointed relief agent for the state, David Wills. The idea of a national cemetery was not new; an 1862 law authorized the President to purchase land for national cemeteries and by 1863 there were at least twelve in existence. This proposal was approved and requests for support sent to the governors of the affected states. In the meantime, Wills began looking for a location to set the cemetery. Since David McConaughy had already offered the state land in Evergreen Cemetery, Wills began approaching landowners there to purchase land for the cemetery. However, many of the neighboring landowners had already promised their land to McConaughy and would not break their agreements in favor of the state, so Wills accepted defeat and found a new location on the north end of Cemetery Ridge on Judge David Zeigler’s property. Eventually, Wills and McConaughy reached an agreement in August that Evergreen Cemetery would sell a total of seventeen acres to the state for $175.

On August 10th, Major General Darius Couch ordered that no battlefield disinterments be allowed during the months of August and September. This was mainly to halt the removal of bodies by families in the heat of summer, but it also stalled the reinternment process for the national cemetery. The design process moved ahead, however, under the supervision of landscape gardener William Saunders of the US Department of Agriculture. He designed a landscape of “simple grandeur” with low, semi-circles of graves surrounding a central monument and a careful selection of foliage. Saunders laid out the cemetery so that burials were separated into sections by state and soldiers and officers were buried on an equal footing. The dedication was also set for November 19, 1863 based on the availability of the chosen speaker, Edward Everett.

On October 13, 1863 Wills published a notice in the Adams Sentinel that any family wishing to claim remains needed to notify him at once since the bodies would not be moved from the cemetery once buried there. He also put out a call for bids to disinter the dead from the field and reinter the bodies in the new cemetery and received thirty-four responses ranging from $1.59 to $8 per body. The winning bid came from Frank W. Biesecker who was contracted to complete the entire job. Biesecker hired teamster Samuel Weaver as superintendent for the exhuming of bodies from the battlefield. Weaver supervised every disinterment himself, ascertained whether the remains were Union or Confederate, searched for clues of the man’s identity, and packaged any personal effects found in the grave for the family. Basil Biggs and a team of eight to ten helpers assisted Weaver by transporting empty coffins from the train station to the burial sites, helping disinter bodies, and bringing the full coffins to the cemetery site. At the cemetery James S. Townsend, Surveyor and Superintendent of Burials, worked under Saunders to lay out the plots and mark each grave while Biesecker and gravedigger John B. Hoke dug the graves and placed the coffins. At the end of each day Weaver and Townsend compared their records and gave them to David Wills for the permanent register of burials.

Even though Weaver delivered up to one hundred bodies a day to the cemetery, the work was not complete by the November 19 dedication. When Abraham Lincoln gave the Gettysburg Address he looked from a platform in Evergreen Cemetery over an unfinished cemetery with freshly dug graves and a great deal of work still to be done. It would not be until the following spring that the team would finish moving all the Union bodies to the cemetery and then the stonecutters could come in to engrave and lay the headstones. The crowning monument to grace the center of the cemetery was finally finished and dedicated in 1869. The completed cemetery held 3,354 internments with 1,664 graves labeled “unknown.” Some unknown burials could be identified by state and lie within their state’s section while 979 unknown burials lie in their own separate section. In total the project to develop Gettysburg National Cemetery cost $80,000.

Further Reading:

Coco, Gregory A. A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg: The Aftermath of a Battle. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 1995.

Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic of Suffering. New York: Alfred A. Kopf, 2008.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.