Illegal Lincoln? Abraham Lincoln and Habeas Corpus

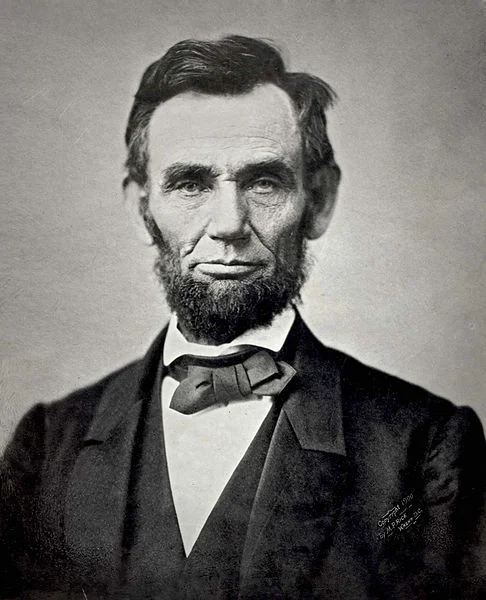

/In the pantheon of American civic and political heroes, Abraham Lincoln surely ranks near the top. The humble lawyer from Illinois became the leader of the fledgling United States in its darkest hour, skillfully maneuvering her through four nightmarish years of civil war. Lincoln is widely considered to be the greatest American president, one who never lost sight of his goal of preserving the Union and one who succeeded in that noble cause.

Yet Lincoln, who in our collective memory resounds as a strong, certain and triumphant leader, was forced to make incredibly difficult decisions throughout the Civil War, and some of these decisions have not always been applauded. Lincoln may have, as some scholars have put it, a “dark side.” His actions were not always approved of at the time; in fact, Lincoln decried as a tyrant in many quarters. In the spring of 1861, President Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus in Maryland—allowing American citizens to be locked up indefinitely without the opportunity of a trial. Lincoln’s suspension of the writ stands as one of the strongest uses of presidential power in United States’ history. This post examines not only the crisis in Maryland that led to such drastic (or draconian?) legal steps, but also explores the debate regarding Lincoln’s actions. Three simple questions are then raised and considered: Were Abraham Lincoln’s actions legal? What were his constitutional views that would permit such a bold use of presidential power? Lastly, were his actions justified?

With the firing on Fort Sumter in April, 1861 and the subsequent secession of four more upper-South states, the Union stood in a precarious position. The secession of Virginia in particular proved troublesome, as it threatened the capital at Washington and would perhaps pull Maryland into the Southern Confederacy as well. On April 19th, the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment marched through downtown Baltimore, headed for the train station and Washington, D.C. A pro-Southern mob formed, angry at the presence of Federal troops in their city. The mob grew violent, the nervous Massachusetts soldiers opened fire, and when the smoke cleared four soldiers and twelve citizens lay dead. Within the following days, telegraph lines and railroad connections into the city were cut by secessionists. Maryland stood on the brink of secession, Washington D.C. was isolated from the rest of the North, and the Union hung in the balance.

In the midst of this turmoil, President Abraham Lincoln acted decisively. While Maryland collectively leaned Unionist, Baltimore was obviously a seething cauldron of secessionist dissent, and Washington D.C. was threatened by the ability of Baltimore to cut off communications with the North. Therefore, on April 27, 1861, President Lincoln ordered the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus “at any point on or in the vicinity of the military line [railroad]” which headed north through Maryland; the orders were generally kept private, sent to military commanders only. This bold step was a grave exercise in presidential power. Lincoln’s suspension of the writ cannot be overestimated. The President was in short authorizing the military to lock up troublemakers and throw away the key.

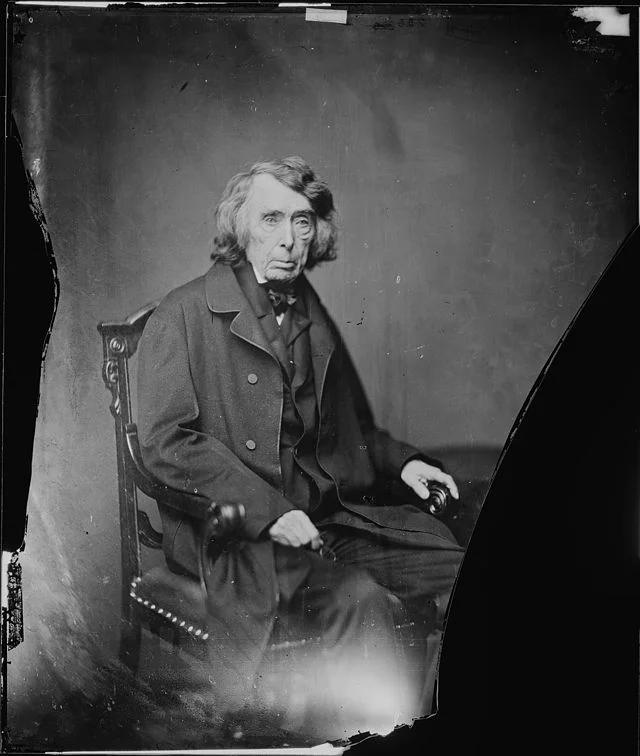

Yet Lincoln’s suspension of the writ in April of 1861 was not to go unchallenged. No one had bothered to notify the judiciary that Lincoln was suspending the writ, and this did not set well with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of the United States Supreme Court, who complained, “No official notice has been given to the courts of justice or to the public by proclamation or otherwise that the President claimed this power.” Taney, who had presided over the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision, challenged the President’s suspension of the writ in a court case, ex parte Merryman. John Merryman was an early casualty of the suspended writ. Merryman had been locked up under suspicion of burning bridges, cutting telegraph lines, and helping to organize a pro-Southern militia. Despite Chief Justice Taney’s attempt secure the release of Merryman via a writ of habeas corpus, the military rejected the writ (as per Lincoln’s orders), and Merryman continued his imprisonment.

Taney’s ruling in ex parte Merryman criticized the Lincoln administration, finding its actions to be unconstitutional on several grounds. First, he argued that the power to suspend the writ was found not within Article II of the Constitution (the executive), but instead was under Section 9, Article I of the Constitution and therefore fell under the purview of Congress. Taney cited previous Chief Justice John Marshall as stating, “If at any time, the public safety should require the suspension [of the writ of habeas corpus]…it is for the legislature to say so.” Lincoln did not have the constitutional power to suspend the writ; Congress did. As Taney chastised, “I can see no ground whatever for supposing that the President, in any emergency or in any state of things, can authorize the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or arrest a citizen, except in aid of the judicial power.” Second, by suspending the writ, Lincoln had also failed to provide John Merryman with the due process of law.

Lincoln’s response to Taney’s ruling (though he never said specifically to whom he was addressing, it was commonly understood to be Taney) is quite famous, and much can be read into it:

…To state the question more directly, are all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken, if the government should be overthrown, when it was believed that disregarding the single law, would tend to preserve it? But it was not believed that this question was presented. It was not believed that any law was violated.

Clearly, Lincoln felt that national security (preserving the Union) and thereby upholding the existence of the government and its body of laws, trumped the importance of upholding one single law. Yet if Lincoln truly believed that no laws had been broken, why would Lincoln feel the need to defend his actions? Historian James G. Randall has concluded that Lincoln had significant doubts about the legality of his actions, and those doubts are reflected in his writings (thus, Lincoln defends a hypothetical scenario). Further, Lincoln highlighted the improbability of convening Congress and suspending the writ quickly enough to respond to an emergency. “[I]t cannot be believed the framers…intended,” Lincoln queried, “that in every case, the danger should run its course, until Congress could be called together.”

Despite whatever doubts he may have possessed, Lincoln defended his suspension of the writ and simply ignored Chief Justice Taney’s ruling. It is interesting to note that the use of suspended writs only continued to grow as the war continued, and Lincoln in fact began to delegate the “writing of the orders and proclamations suspending the writ…a sure sign of indifference”. Lincoln grew confident in his ability to suspend the writ as the war dragged on.

While Lincoln had both responded to and ignored Chief Justice Taney, he also had to explain himself to Congress, to whom the authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus clearly did belong. In July of 1861, Lincoln defended his actions to Congress in much the same way as he had responded to Taney. As noted historian Philip Shaw Paludan has argued, Lincoln’s responses seem to suggest that he believed he “might execute a law before Congress passed it,” if he felt that Congress would approve afterwards. Congress did approve of his actions, which was perhaps partly the cause of Lincoln’s willingness to continue suspending the writ throughout the war. Indeed, thousands of citizens would be arrested without the writ by war’s end, although many of them hailed from Confederate or border states.

Thus, Abraham Lincoln perhaps broke the law. And perhaps he knew it. But he would continue to suspend the writ as the war dragged on. What, then, allowed Lincoln to take such powerful executive steps? What were his justifications for continually toeing the legal line?

The great biographies of Abraham Lincoln give us only the briefest glimpses into Lincoln’s constitutional thoughts regarding his bold actions in Maryland. David Herbert Donald’s Lincoln provides a brief account of the incident, giving the impression that Lincoln could not address the legal counter-arguments against his actions and thus simply ignored them. Carl Sandburg’s much vaunted volumes on Lincoln also paint a quick portrait, highlighting Lincoln’s famous quip, “Are all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated?” This initial response by Lincoln satisfies Sandburg, who provides little analysis on the response and how it can be interpreted regarding Lincoln’s personal views.

Yet both Donald and Sandburg’s works are classical biographies. Several works exist that focus specifically on Lincoln and the Constitution. Historian Mark Neely, Jr. concludes that Lincoln had doubts about his legal, constitutional ability to suspend the writ, but over time grew comfortable with and perhaps indifferent to the writ’s suspension. However, Neely also defends Lincoln’s use of the writ as being strictly for military, not political purposes. While all the authors previously mentioned are noted historians, work by Daniel Farber grants us the vantage point of a political scientist. Farber focuses less on Lincoln’s personal thought process, but more on the constitutionality of his actions. Farber finds Lincoln’s actions “constitutionally appropriate,” though he notes they can “hardly be considered free from doubt.”

Many historians have been defenders of Lincoln’s suspension of the writ, or at least forgiving of it; Joshua Kleinfeld’s work stands in stark contrast to this trend, as he argues that Lincoln clearly violated the Constitution and threatened civil liberties. Brian Dirck argues that Lincoln, with his law background, felt most comfortable making these Constitutional decisions (as opposed to military ones) and showed himself to possess a “broad constructionist interpretation” of the Constitution.

Despite the possibility of Maryland legislators convening to secede, Lincoln only suspended the writ to keep military lines with the North open; thus, as Mark Neely argues, Lincoln only used the suspension of the writ for military purposes only, not for political gain. This strict use of executive power for military use only is also exemplified by Lincoln’s refusal to use his powers to challenge voting rights; he allowed anyone to vote, including in the 1864 election which was essentially a “referendum on the war,” a referendum on which the fate of the nation depended.

We return then to our three original questions—was Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus legal? What constitutional viewpoint did Lincoln possess that allowed such bold executive action? If Lincoln’s actions were not constitutional, was he justified in the suspensions regardless? Ultimately, Lincoln clearly ignored a Supreme Court ruling (which via judicial review is the final arbiter of constitutionality) that revoked his power to suspend the writ as unconstitutional. Daniel Farber, political science professor at the University of California-Berkeley, concedes that Lincoln’s failure to adhere to Taney’s ruling was likely unlawful; executive nullification can’t be argued for, nor did Lincoln argue for it.

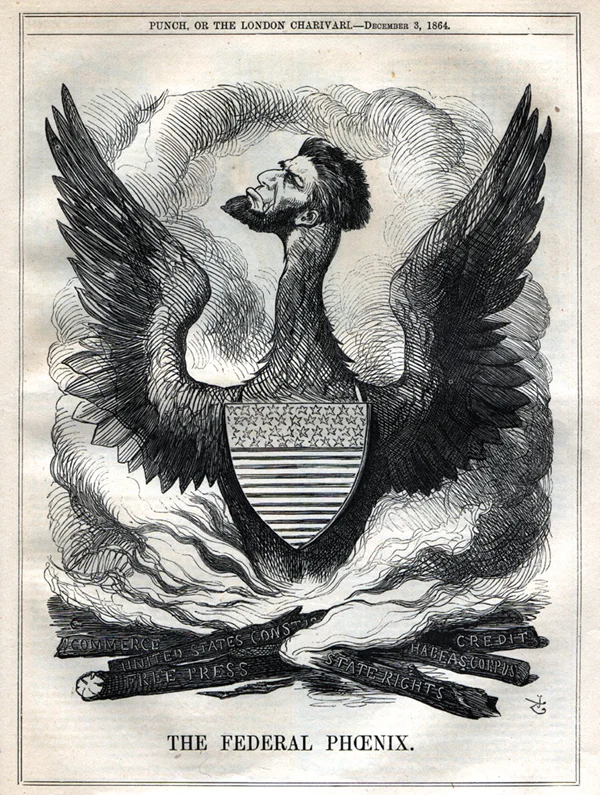

Taney’s ruling was based on precedent. John Marshall had noted that the power to suspend the writ “is for the legislature,” and Joseph Story, another former Supreme Court Justice had also stated that the “power is given to congress to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in cases of rebellion or invasion…[and] must exclusively belong to that body.” There was a clear standing in American legal tradition and precedent that the power of suspension went solely to Congress. As Joshua Kleinfield succinctly argues, “Taney’s textual argument would stand. Lincoln was not constitutionally entitled to suspend the writ of habeas corpus.” The result, in Kleinfield’s view, was the weakening of civil liberties and enhanced executive power. First, Lincoln increased the power of the executive by ignoring a Supreme Court ruling that should have been binding. Second, “Lincoln seized a power which the Constitution considered too dangerous to be in the hands of a president,” setting a dangerous precedent and creating the possibility of future power grabs by the executive in the future (along with the ability to ignore the judiciary while doing so).

Yet while Kleinfield and Taney may agree, other historians do not. Brian Dirck sees legitimacy in Lincoln’s exercise in power, as Lincoln possessed “a broad constructions interpretation of his own powers as commander-in-chief. What he posited here was not lawless tyranny, but a lawful, and very expansive, reading of the Constitution…” Lincoln also countered the hypothetical illegality of his actions by referencing his duties as listed in the presidential oath of office. He considered his duty to uphold and protect the Constitution to be greater than the execution of any single law. Lincoln himself phrased this famously in an anecdote, “Was it possible to lose the nation, and yet preserve the constitution? By general life and limb must be protected; yet often a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely give to save a limb.” If Washington D.C. had fallen to the Confederacy, or Maryland seceded with the rest of the South and the Union had been dismantled, Lincoln would have failed in his duties as president and commander in chief. Such a chain of events was certainly plausible. Lincoln’s arguments justifying his actions fall in line with the traditional definition of necessary emergency powers; simply put, he had to choose between the lesser of two evils (fall of the Union or suspension of the writ). As famed historian James McPherson noted, Lincoln felt strongly that his chief obligation as commander in chief was to preserve the Union, and that single objective overrode all other Constitutional concerns.

Thus, answers seem to have emerged for the first two questions. In the strictest sense, Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus was likely unconstitutional, unless one takes an incredibly interpretive view of the document. Clearly, ignoring Chief Justice Taney’s ruling regarding suspension of the writ was illegal. Thus, Lincoln clearly skirted along the line of constitutionality in suspending the writ of habeas corpus from 1861 onwards.

Lincoln held constitutional viewpoints that justified his strong, albeit controversial, executive actions. First, his broad interpretation of the executive power, especially in drawing upon the presidential oath and his role as commander in chief in wartime, allowed him to stretch the limits of executive power. He acted independently and quickly in times of crisis, in ways he assumed Congress would approve. Second, Lincoln took a very practical approach to the use of presidential power. He felt strongly that his duty to preserve the Union and its government overrode any other Constitutional obligations or restrictions. Survival of the nation came first. This similarly ties into his apparent acceptance of the concept of emergency powers for the executive (which could much more swiftly deal with crisis than Congress). This is noteworthy, for as Brian Dirck points out, it also suggests that Lincoln did not act on any “program or system of thought. There was no “Lincoln Doctrine” concerning how a president should conduct a war.” Lincoln acted as the circumstances required, varying his actions to the situation, but always with the goal of preserving the Union.

The last question, then, is whether Lincoln truly was justified to break the law, indeed the Constitution? Do his justifications have merit? The question is, to a certain extent, a counterfactual one; the outcome of the crisis had Lincoln not suspended the writ of habeas corpus is unknown. Yet no greater emergency exists than civil war, whence the very survival of the state is at stake. Further, it does become clear that Lincoln, despite his unconstitutional actions, possessed great respect on the Constitution and put much thought into his actions. As Philip Shaw Paludan notes, “Lincoln consistently placed himself within constitutional limitations.” This is evident even when Lincoln suspended the writ, for immediately following the crisis he submitted himself to Congress, both in explanation and review.

Ultimately, Abraham Lincoln faced an extraordinary national emergency in the spring of 1861, one that threatened the very existence of the United States itself. In response, he took extraordinary, albeit extra-Constitutional, steps to secure the nation. While some of Lincoln’s actions clearly seem to fall outside the law (particularly ignoring a Supreme Court ruling), his broad constitutional interpretation and pragmatic approach to the situation, namely placing the security and survival of the nation over the execution of a single law, allowed him to exercise unprecedented executive power. While the alternatives are unknown, Lincoln’s actions did help secure Washington D.C. and Maryland, which went a long way towards the preservation of the Union. Lincoln’s use of extra-constitutional power seems to be justified due to the extraordinary emergency crisis the nation faced, his limited use of suspension of the writ of habeas corpus (only for military use), the immediate explanation justifications of his actions to Congress, and finally his larger respect for the Constitution in general.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Sources and Further Reading:

Dirck, Brian. “Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief.” Perspectives on Political Science 39, no. 1 (Jan.-Mar., 2010): 20-27. http://web.ebscohost.com (accessed November 15, 2011).

Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Ewers, Justin. “Revoking Civil Liberties: Lincoln’s Constitutional Dilemma.” USA Today online, (Feb. 10, 2009). http://www.usnews.com (accessed November 16, 2011).

Farber, Daniel. Lincoln’s Constitution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Kleinfield, Joshua. “The Union Lincoln Made.” History Today 47, no. 11 (Nov., 1997): 24-30. http://web.ebscohost.com (accessed November 15, 2011).

McPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

---. Tried By War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief. New York: Penguin Press, 2008.

Neely, Jr., Mark E., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Paludan, Phillip Shaw, “‘Dictator Lincoln’: Surveying Lincoln and the Constitution.” Organization of American Historians Magazine of History 21, no. 1 (Jan., 2007): 8-13. http://web.ebscohost.com (accessed November 15, 2011).

Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln. 3 Vols. New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1954.