When Battlefield Killing Becomes Murder: Antietam and Fredericksburg

/Marching in column after column upon the enemy’s works, only to be mowed down and driven back—again to re-form and close up their broken ranks, and once again, with steady step to face the storm of death. And thus over and over again they repeated their noble, but alas, fruitless deeds of valor, until divisions assumed the proportions of brigades, brigades of regiments, and regiments ofttimes had but a handful of brave fellows left, with but one or two commissioned officers remaining able to lead. And so the tide of battle ebbed and flowed until generous night covered the blood-stained field with her sable mantle.

Descriptions such as this one from the Battle of Fredericksburg reveal the nature of Civil War battle. Although this passage seems romanticized for the benefit of its newspaper audience, the horror of fruitless and vain charges against the enemy comes to the surface. The Battle of Fredericksburg, and indeed the last few months of 1862, shows the beginning of an increasingly shocking mode of warfare in the Civil War. Soldiers had to do more than just describe battles to audiences and loved ones back home, they had to describe and rationalize them for themselves. It is well understood that those who join the military or serve in wartime see and experience things which test their strength, courage, and even sanity. While each war is different in motive, technology, and character, each place the same burden on the human beings fighting it. The human mind has not changed in the way it filters and manages the experiences it faces, so soldiers typically react in the same way through history. Psychologists have attempted to pinpoint the process used to handle the types of stress soldiers encounter in war and on the battlefield, and now military historians are utilizing this information to better understand how soldiers through history have coped. This article uses the battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg as a case study to understand how Union soldiers reacted to the large scale killing and casualty rates of Civil War combat. While both battles resulted in a high number of casualties, the responses from Union soldiers were fundamentally different between the two battles. The difference in reactions suggest that soldiers rationalized and coped with each battle differently as well.

The Battle of Antietam that played out around the town of Sharpsburg on September 17, 1862 marked the climax of Robert E. Lee’s first major push into the North. Lee took the offensive for several reasons: bring the war to the North and influence the upcoming Congressional elections, threaten the Union capital at Washington D.C., give aid to Maryland to convince her to secede, and seek the aid and recognition of foreign powers. In early September Lee crossed the Potomac River and moved into Maryland, his first offensive move in the war, and Union commander George B. McClellan moved to counter him. After the capture of Harpers Ferry and the Battle of South Mountain, Confederate and Union forces converged on the town of Sharpsburg alongside Antietam Creek.

The battle flowed from north to south along the creek in three phases. At dawn the battle opened between Joseph Hooker’s Union I Corps and Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson’s Confederates. These men and their reinforcements fought through the North, East, and West Woods, the infamous Cornfield, and in the vicinity of Dunker Church. By midday, the battle had shifted south to the center of the Confederate line where the Dunker Church saw more fighting and the two sides struggled over a small farm lane later to be renamed Bloody Lane. The finale of Antietam occurred on the southern end of the battlefield as Ambrose Burnside attempted to cross his IX Corps over a narrow bridge to attack Confederate James Longstreet’s troops. After several attempts, his men crossed and attacked the enemy but became disoriented and ineffective and had to withdraw. Despite McClellan’s advantage in manpower, his plans were poorly coordinated and executed and the terrain made it difficult for officers to coordinate with him and each other. Consequently the battle proceeded in these three, separate phases instead of a concerted effort. The battle raged over the landscape for twelve hours, from five-thirty in the morning to five-thirty that evening, and cost both armies dearly. In total around 23,000 Americans were killed, wounded, or captured/missing (over 12,000 for the Union and over 10,000 for the Confederates). This day went into the history books, and still remains, as the bloodiest day in American history.

Neither side attacked on September 18th and that evening Robert E. Lee began withdrawing his troops and returning to the Confederate soil of Virginia. Neither side could declare complete victory, but the Union held the field at the end of the encounter, giving President Abraham Lincoln enough confidence to announce his plans for the Emancipation Proclamation and giving foreign powers pause in their interest of supporting the Confederacy. Despite his advantage, however, McClellan did not vigorously pursue the retreating enemy. Instead, they safely slipped back over the Potomac River and the Maryland campaign was over. A disappointed Lincoln relieved McClellan of his command on November 7, 1862 and turned his focus to a new military leader with the hopes of better success.

The man Lincoln chose to pick up the reigns of the Army of the Potomac was Ambrose E. Burnside, who had seen success in the Carolinas and led the IX Corps at Antietam. As Burnside took command from McClellan on November 7, Lincoln’s message was clear. The Union needed a clear military victory in advance of the January 1, 1863 release date for the Emancipation Proclamation. In response, Burnside planned an offensive to begin that very month, moving through the City of Fredericksburg, Virginia, along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railway, and on to the Confederate capital of Richmond. He needed to move swiftly, both for Lincoln’s political aims and to ensure less Confederate resistance along the way. However, his plan hit a snag almost immediately: the Rappahannock River running alongside Fredericksburg. The three bridges that once spanned it were gone, destroyed that summer by retreating Confederates before the Union army occupied the city prior to the Maryland Campaign. Now Burnside needed administrators in Washington D.C. to send his army portable pontoon bridges to be able to cross and continue his offensive. The Army of the Potomac arrived much earlier than the needed supplies and by the time the pontoons arrived Robert E. Lee and his army were entrenched on the other side of the river in opposition.

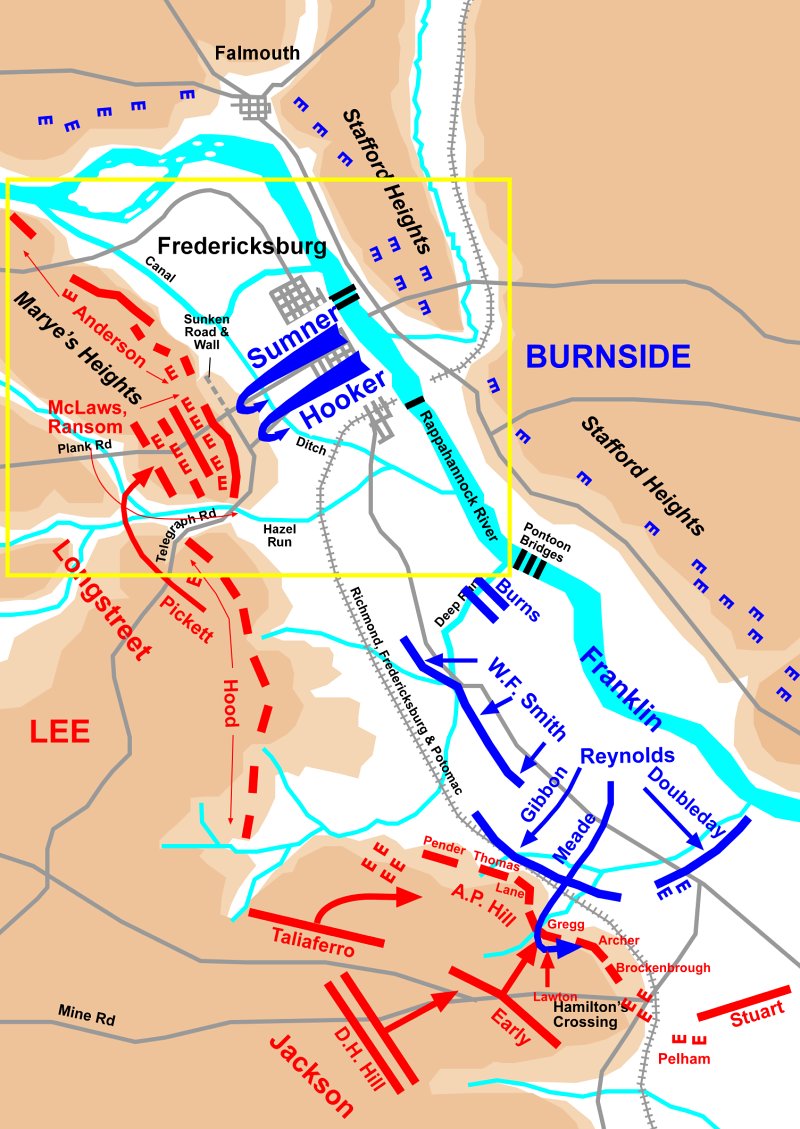

Weighing his options, Burnside decided to stay with his original plan and cross directly opposite the city of Fredericksburg. The other crossings up and down river were guarded by Confederates, he though Lee might least expect an attack on the city, and Lincoln expected a strong and victorious show of force. On December 11, Union engineers began constructing pontoon bridges at three locations under the cover of the morning fog. Their task was not completed by the time the fog cleared allowing Confederates hiding in the town to fire upon the bridge builders. December 11, 1862 saw the first riverine amphibious landing under fire of United States troops as soldiers piled into pontoon boats and poled across the river to meet the enemy and the first case of street-to-street fighting as Union and Confederate soldiers battled in streets, alleys, and houses. By the end of the day, the Union held the town but the Confederates had managed to seriously delay Burnside’s battle plan.

Burnside’s plan for December 13, 1862 was not a “bad” plan, however it quickly devolved into a military disaster. He would send a diversionary attack from the town of Fredericksburg against the Confederate line holding the base of Marye’s Heights just outside town while his main force would attack the other end of the Confederate line four miles to the south at Prospect Hill. If they could take Prospect Hill they could continue on their way to Richmond as planned and cut Lee off from his capital city. Immediately plans went awry, however, as the officer commanding the main attack, Major General William B. Franklin, confused his orders, sent only 8,000 men into the attack, and began the offensive late. This small group of men led by Major General George Gordon Meade successfully broke the Confederate line, but did not have adequate force to hold the breach. Burnside’s main attack failed and would not be renewed. Meanwhile, diversionary attacks continued at Marye’s Heights in support of Franklin’s now-failed assault on Prospect Hill.

The attacks on Marye’s Heights horrified the soldiers fighting there or witnessing the action, and they continue to horrify scholars and visitors today. Seven attacks, each consisting of two to three lines of men, were send up the long open landscape to be mowed down by Confederate artillery on top of the heights and infantry concealed behind the protection of a stone wall. At least half of these attacks occurred after the Prospect Hill fight was over—while this occurred because Burnside expected Franklin to renew the assault it has called into question his judgment as a commander—and continued until night fell over the field. Even then soldiers of both sides were pinned on the field until the night of December 15th when Burnside finally ordered a retreat. The Battle of Fredericksburg was decidedly a Confederate victory, but the slaughter at Marye’s Heights handed Robert E. Lee the most lopsided victory of the war. The Union army lost 12,527 casualties, around 8,000 of them at Marye’s Heights, and the Confederates lost under 5,000 men, with only 1,500 of them at the Heights. That is a ratio of 8:1 at Marye’s Heights and 12:5 for the whole battle.

With many bloody and disastrous battles in the American Civil War, in the battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg we see the bloodiest day of the war and of American history and one of the worst disasters for the Union army. These two battles come at the end of 1862, the second year of a war that now experienced a harsh transition. By this point all hopes for a quick resolution of the conflict, of a short war, were extinguished. The politicians, civilians at home, and soldiers on the front lines all realized that this war was going to be long and bloody. Starting with battles like Shiloh in April 1862, soldiers experienced a more brutal and bloody warfare with immense casualty rates unimagined at the start of hostilities. Antietam and Fredericksburg are examples both of high casualties and of high impact. Antietam as the bloodiest single day of the war deeply impressed the armies and nation that warfare was changing, but it is also considered one of the war’s turning points due to the subsequent issuance of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and its impact on the decisions of Britain and France to not officially recognize the Confederacy. The Battle of Fredericksburg saw roughly five thousand less casualties than Antietam but because of the futility of the action and the open landscape soldiers were more affected by the horrors of war there than in other battles. The significance of both battles partially lies in the casualties.

Soldiers might be hardened in the moment, but the aftermath required a different coping process. The single day of carnage at Antietam produced scenes which disgusted and horrified those who attended to the field after the fighting ended. A chaplain with the 102nd Pennsylvania called the battlefield a “vast Golgotha—that modern Aceldama—a real field of blood.” Soldiers faced with the “terrible wreck and ruin of the great battle of this war” found the sight of dead and wounded men the worst to bear. G. R. of the 16th Connecticut thought of the families back home as he traversed the battlefield where “scattered here and there, were the marred and now offensive bodies of those who had been the light of many a household.” Losing 150 men out of 280 engaged was the “most dreadful slaughter” one regiment saw in the war. Rufus Dawes from Wisconsin continued in his post-war memoir to claim Antietam as the worse slaughter he had seen, even past his own regiment:

The piles of dead on the Sharpsburg and Hagerstown Turnpike were frightful. The “angle of death” at Spottsylvania (sic), and the Cold Harbor “slaughter pen,” and the Fredericksburgh (sic) Stone Wall, where Sumner charged, were all mentally compared by me, when I saw them, with this turnpike at Antietam. My feeling was that the Antietam Turnpike surpassed all in manifest evidence of slaughter.

Even with such description, the focus remains on legitimate casualties. Antietam was a hard fought battle, and the evidence lay about these soldiers in mass quantities, but these casualties were the result of intense close combat over the course of twelve hours. Despite the large casualty numbers, soldiers could rationalize these deaths as legitimate. Similar to the Battle of Shiloh examined by Frank and Reaves, morale would be low immediately after the battle when the destruction described by these soldiers is clearly evident. Morale would rise, however, as the army moved on. Frank and Reaves argue that even after the types of casualties seen at Shiloh—23,000 over two days, at that point the costliest battle of the war—the soldiers were resilient and not permanently damaged by the death toll.

In a situation where the enemy had no chance, was performing normal duties away from the lines, or was defenseless, their death became problematic. For example, sharpshooters gained the intense hatred of most soldiers because they targeted one particular victim, usually at a time where that person was not a direct threat to the killer. This reaction was not restricted only to sharpshooters; William Fisk looked askance at the actions of a comrade:

Occasionally a secesh could be seen scampering over their works as if on an errand of life and death, and I have no doubt they were. My nearest comrade, noticing one bold fellow walking leisurely along in open defiance of our bullets, drew up his faithful Springfield and taking deliberate aim—I fear with malice aforethought and intent to kill—fired. My friend is a good marksman, and as secesh was not seen afterwards, the presumption is that he had an extra hole made through his body.

Soldiers saw this type of action as murder. John G. Perry, upon witnessing a sharpshooter’s success, commented that the shot was “remarkable” even with the aid of a scope, but that he was “thankful to say that every man who witnessed the act pronounced it contemptible and cowardly.” The individual targeting of an enemy soldier or killing enemy soldiers who cannot defend themselves was crossing the line of “legitimate” death in war.

The sentiments about the Battle of Fredericksburg reflect this distinction in battlefield death. This battle, particularly the fighting on Marye’s Heights proved to be fruitless, frustrating, and impossible. Lines of men charged the impenetrable stone wall and reeled back broken. “Wave after wave of stout hearts was rolled against their immense fortifications, and was lost for ever,” wrote a soldier correspondent for the Irish American Weekly. “Impossible it was to carry the heights with the point of the bayonet; yet West Point Generals said they should be carried at any cost. Another charge and another slaughter, still the enemy held his ground.” The persistence of their commanding officers produced a situation which many Union soldiers defined as unnecessary killing, unnecessary death. The battle on Marye’s Heights left the realm of acceptable warfare, and became murder. A member of the 13th Massachusetts, stationed elsewhere on the field and learning of the situation later, remarked, “If ever men in this war were slaughtered blindly, it was there.” One colonel became so overcome at the scene playing out in front of his eyes that he threw his arms around fellow officer George Barnard and “almost cried at this wicked murder.” Barnard himself was affected. “[I]t is no satisfaction to me,” he continued, “that I led brave men to useless death.” Even their enemy agreed with the nature of Marye’s Heights. A Confederate posted on the opposite side of the plain commented on his position: “Should the [Union] infantry attempt to assail our position on these hills they might start ten thousand at the foot of them, and not one would reach the top. It would be like murder to kill them in such a place.” The writer, Edmund DeWitt Patterson, was correct; no Union soldier ever reached the Confederate line at the Sunken Road. Participants and survivors of the Union attack on this portion of the battlefield were upset and depressed by this seemingly wasteful loss of life, which in the end gained the Union nothing but embarrassment and infamy. “It was simply murder,” wrote John L. Smith of the 118th PA Infantry, “and the whole army is mad about it. We are no fools! we can see when we have no chance; here we had none.” In this case, the killing expected in warfare turned into murder because of the hopelessness of the situation and the defenselessness of the Union soldiers charging up the hill. This type of killing and death, seen in such a large scale in one battle was harder for soldiers to rationalize. Morale in the Union army was low for months after the disaster at Fredericksburg as soldiers struggled to cope with the situation they had experienced.

The difference in reactions to the Battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg was exaggerated by the difference in terrain. Antietam resulted in a larger number of casualties but the same terrain that made it difficult for McClellan and his officers to coordinate the attacks made soldiers only see their area of the battlefield. Normally, battle is not experienced by soldiers through the wide-scale movements of a battle map, but as small, individual experiences. Soldiers are aware of their regiment or those men in their vicinity, and not much beyond it. Usually their full understanding of the scope of a battle comes afterwards when they travel through the battlefield, if they get an opportunity to do so, or hear stories from other soldiers and newspaper reports. In contrast, the long, open plain before Marye’s Heights meant that soldiers were aware of more than their immediate groups. Both those moving into battle and those witnessing could see the entire battle play out as each attack failed spectacularly. The wide view led to soldiers making extravagant claims about the casualties, since so many dead and wounded were massed in a concentrated area. It also meant that Marye’s Heights left a lasting impression on the soldiers who fought there or saw the action. That so many men had witnessed the large scale death and killing on those Fredericksburg plains increased the horror associated with the battle.

The two battles examined here were both extreme in their own way. With large casualty rates and the high impact of the results, soldiers would have to filter what they saw and experienced through the psychological processes historians and psychologists are trying to uncover. While this article did not delve into how Union soldiers specifically used the psychological processes examined above to cope with their experiences at Antietam and Fredericksburg, it revealed that reaction and response varied between engagements. The manner in which a soldier defined, explained, and rationalized a specific battle would affect their ability to cope with that experience. Despite seeing similar high levels of casualties, responses to Antietam and Fredericksburg were very different. Consequently how they utilized the coping method might be different as well. Soldiers’ ability to rationalize the deaths at the Battle of Antietam allowed them more chances at successfully coping with the experience than after the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

Acken, J. Gregory. Inside the Army of the Potomac: The Civil War Experience of Captain Francis Adams Donaldson. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998.

Barrett, John G., ed. Yankee Rebel: The Civil War Journal of Edmund DeWitt Patterson. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2004.

Bourke, Joanna. An Intimate History of Killing: Face to Face Killing in 20th Century Warfare. BasicBooks, 1999.

Dawes, Rufus R. Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers. Edited by Alan T. Nolan. The State Historical Society of Wisconsin for Wisconsin Civil War Centennial Commission, 1962.

Dean, Eric T., Jr. Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

Frank, Joseph Allan, and George A. Reaves, “Seeing the Elephant”: Raw Recruits at the Battle of Shiloh. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Gabriel, Richard A. No More Heroes: Madness and Psychiatry in War. New York: Hill and Wang, 1987.

Grossman, Lt. Col. Dave. On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society. New York: Back Bay Books, 2009.

Hess, Earl J. The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat. Lawrence, KS: The University Press of Kansas, 1997.

Holmes, Richard. Acts of War: The Behavior of Men in Battle. New York: The Free Press, 1985.

Keegan, John. The Face of Battle. New York: Penguin Books, 1976.

Murfin, James V. The Gleam of Bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s Maryland Campaign, September 1862. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

O’Reilly, Francis Augustín. The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Rable, George C. Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

---. “It Is Well That War Is So Terrible: The Carnage at Fredericksburg.” In The Fredericksburg Campaign: Decisions on the Rappahannock, 48-79. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Rosenblatt, Emil, and Ruth Rosenblatt, ed. Hard Marching Every Day: The Civil War Letters of Private William Fisk. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1992.

Schantz, Mark S. Awaiting the Heavenly Country: The Civil War and America’s Culture of Death. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1983.

Shalit, Ben. The Psychology of Conflict and Combat. New York: Praeger, 1988.

Stewart, Rev. A. M. Camp, March and Battlefield; or, Three Years and a half with the Army of the Potomac. Philadelphia: Jas. B. Rodgers, Printer. 1865.

Also:

Collection of John Hennessey, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

SoldierStudies.org.

Barnard Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society [Reel 17 of Civil War Correspondence, Diaries, and Journals].

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, BV44; Correspondence with Park Historian Donald Pfanz, October 4, 2012.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.